Before marrying, Kenyans check out all manner of qualities. Some men consider looks, smile, fidelity, sexual compatibility, compassion, respect, size of butt as well as boobs. Women size up intelligence, kindness, generosity, virility, sense of humour and whether the wallet can be mistaken for a bible - but not necessarily in that order.

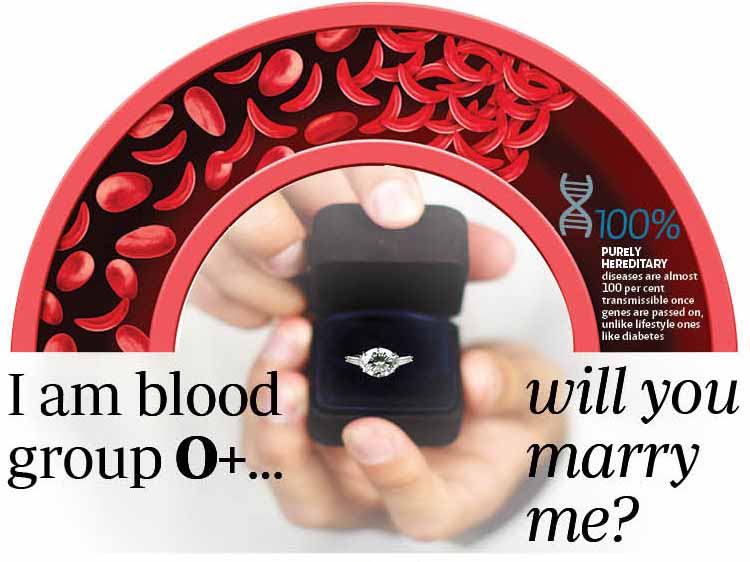

Other attributes which can melt mountains include religion, ethnic extraction, attitude towards money, occupation, in-laws and family history. But rarely do couples consider each other’s medical history beyond HIV status, sometimes with sickly consequences, mostly from hereditary diseases, cases of mental illness, incompatible blood disorders, cyst fibrosis and genetic nerve disorders.

Take Kevine Odunga. She married George Odunga in 1997 and the couple was shortly thereafter blessed with a baby girl who six months later began suffering from persistent malaria and severe pain. Her body would turn pale. The baby was diagnosed with sickle cell anemia, but was electrocuted and died in 2006.

Facts First

Unlock bold, fearless reporting, exclusive stories, investigations, and in-depth analysis with The Standard INSiDER subscription.

Already have an account? Login

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.