On September 25, 2011, Kenya lost her first and only Nobel Laureate, Wangari Maathai, aged 71, and has never forgiven cancer for taking her heroine away.

Around the same time, the country also lost their "charcoal-to-gold" tycoon Njenga Karume, 83, to same killer. As if that was not enough, Kenyans also learnt that their then two Health ministers, Beth Mugo and Anyang' Nyong'o, were also being treated for cancer.

These developments forever changed Kenyans' perception of cancer from a distant 'rumour' to an immediate and present danger lurking everywhere and just waiting to pick on them or their loved ones.

No wonder cancer became a major campaign agenda for the 2013 General Election, with aspiring governors for the 47 counties promising to put up cancer treatment units in their respective regions if elected.

"Cancer evokes fear because of the high cost of treatment, extended suffering, pain and high death rates compared to other diseases," says Prof Nicholas Abinya of the University of Nairobi (UoN).

He explains that unlike other diseases, cancer does not travel along poverty lines - it is a threat to all and sundry. Kenyans, particularly the well-to-do, live well beyond their 70s, with ageing being established as the single biggest risk factor for developing cancer. Life expectancy for Kenyans is estimated at 63 years.

To indicate how seriously the Government is taking cancer, Sh21 billion out of Sh38 billion will go towards cancer screening equipment in the ongoing health equipment leasing project.

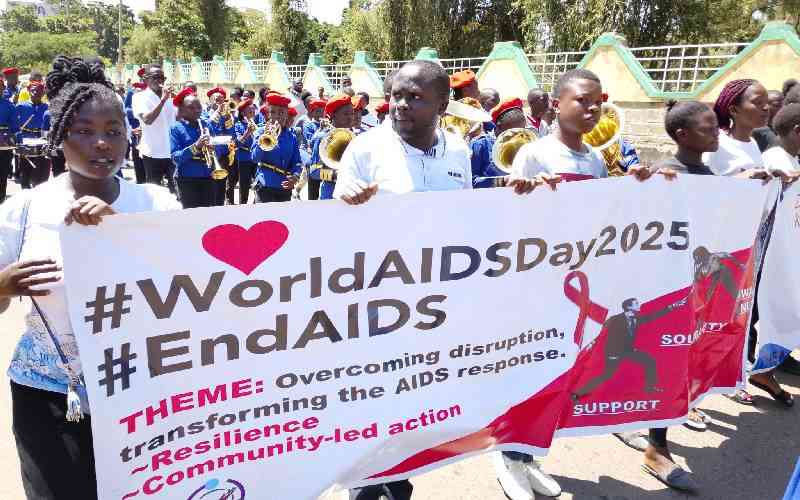

Communicable diseases

But scientific evidence does not justify the panic that has been caused by cancer, which according to the Ministry of Health and the World Health Organisation, is the third biggest killer in Kenya.

While the death toll from communicable diseases and at child birth in Kenya stood at 64 per cent last year, cancer killed seven per cent, slightly less than those who died from heart complications. Of every one person killed by cancer, 65 others die from communicable diseases such as malaria, pneumonia, HIV or tuberculosis.

"While children from middle or upper class families will hardly die of cholera or pneumonia, the poor face the double tragedy of dying from both communicable and non-communicable disease," says Julius Mwangi, a professor of pharmacognosy at UoN.

As the gap between the rich and poor widens, Mr Mwangi says those with medical insurance are most likely to get early diagnosis, which guarantees better treatment results, while the poor may continue dying while waiting for treatment at Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH).

"If it were not for my insurance, a supportive family and colleagues at work, I would be dead today," says Cecelia Omole, a senior officer with a United Nations body and a colon cancer survivor. While the bills never came her way, she estimates spending between Sh4 million and Sh5 million to beat the disease.

Injuries, including from traffic accidents, assault, terrorism as well as heart diseases now cause more deaths than cancer.

"A young man in Nairobi today is many times more likely to die violently than from cancer," says Dr Johannes Odour, the chief government pathologist.

A survey he carried out at Nairobi City Mortuary and the Kenyatta National Hospital in 2013 showed that young males living in Nairobi are at high risk of dying violently from gunshots most likely fired by a police officer, or a traffic accident caused by drunk driving.

"But there is no doubt that cancer is on the increase because of several factors, including poor eating habits, too sedentary a life, alcohol and tobacco abuse, environmental pollution, HIV and other disease causing organisms," says Director of Medical Services Dr Nicholas Muraguri.

The cancer panic that has captured the middle class in the last decade led to a flurry of activities including the development of the first ever Kenya National Cancer Control Strategy 2011-2016 by Mr Mugo and Prof Nyon'go.

The strategy had clear and quantifiable targets to be met by 2016, including reducing the incidence of tobacco abuse by five per cent and obesity by two per cent. The strategy also aimed to have Kenyans increase their intake of fruits and vegetables by five per cent and to cut alcohol consumption by five per cent by next year.

Although a law for the control of alcohol has since been put in place, market figures and a survey by Euromonitor International last year showed Kenyans are drinking more alcohol than ever before.

Physical exercise

A scorecard released by Dr Vincent Onywera of the sports department at Kenyatta University last year showed that children, especially in urban areas, are not doing enough physical exercises and obesity is on the rise in this group.

A study of 5,000 adults in Nairobi in 2013 by the African Population and Research Centre found 43.4 per cent and 17.3 per cent of women and men respectively to be obese or overweight in Nairobi.

"Approximately 40 per cent of cancers are preventable through interventions such as tobacco control, promotion of healthy diets and physical activity," says Prof Abinya.

Prevention, adds Dr Muraguri, is the way to go but we must also put in place an effective treatment programme for those who do get cancer.

However, even with Sh21 billion going to cancer equipment for the next 10 years, it is too little too late.

A health economist based in Nairobi says the leased diagnostic equipment being rolled out in the counties may go a long way in boosting the war against cancer.

"This may address the case of late diagnoses which could lead to better treatment outcomes but since KNH remains the only public health facility offering comprehensive care, the queues may get longer."

The Ministry of Health has also hinted that it might start four comprehensive cancer treatment centres at the Coast, Eldoret, Nyanza and Nyeri.

But this can hardly solve the problem. During its annual scientific conference in October, the Society of Radiography in Kenya estimated that the country requires 56 radiation treatment units to effectively serve the country. Currently, there are less than 10 such centres both in the private and public sectors.

And even for the four proposed sites, the Government will need time to train 125 cancer specialists. These are only 15 radiation oncologists, 25 medical oncologists, 10 radiation therapy technologists, 50 oncology nurses, 10 medical physicists, eight nuclear medicine physicians and 12 nuclear medicine technologists.

While launching the National Cancer Management Guidelines, Health Cabinet Secretary James Macharia said such training would require a huge financial undertaking and could take between one and four years.

"Training may be easier than employing and retaining the best talent in the public sector," says Prof Abinya.

When the Aga Khan University Hospital opened a Sh4.25 billion heart and cancer treatment centre four years ago, it was forced to recruit East African cancer specialists who had migrated to the West at a huge cost.

The Kenya public sector and the counties in particular may find it difficult if not impossible to attract or retain such talent.

Lack of medical engineers, says Dr Rose Nyabanda, head of radiology at Kenyatta National Hospital, in a study, is the cause of poor preventive maintenance of current X-ray and other imaging technologies in the country.

The introduction of the much more effective radiology technology known as linear accelerator at Aga Khan and MP Shah hospitals meant they had to depend on nuclear medical engineers from Europe or the US to service their machines.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.