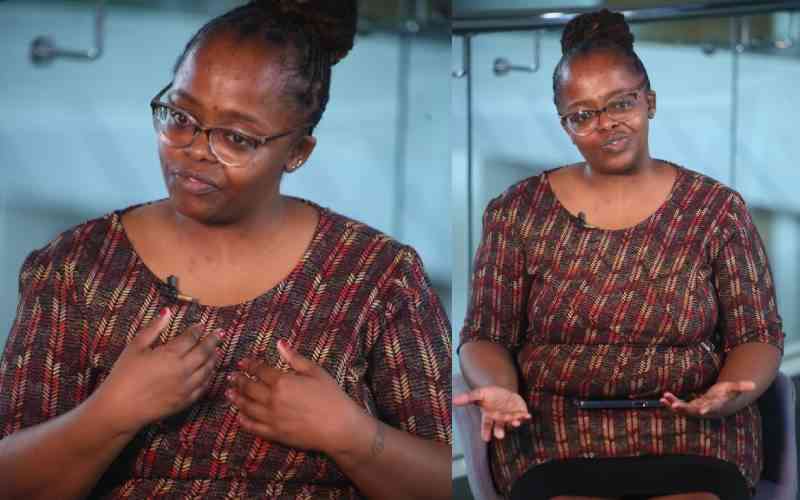

MERCY GICHUNGE, 31, wasn't born with a disability but when she was 10, her life took a new turn. She tells RUTH LUBEMBE why she thinks wearing dresses while playing with her brothers who wore trousers could have caused her present disability.

Inclusion – according to 31-year-old Mercy Gichunge, is the biggest desire for people living with disability. For this to be achieved, society needs to be taught how to treat them. Mercy is on a mission to spread this education.

This is why Disability Awareness Day is celebrated every February in Kenyatta University (KU), five years after Mercy graduated. In addition, KU is today known for having infrastructure in place for the benefit of students living with disability.

"KU remains a benchmark for disability issues in East Africa," she says confidently. "People visit the institution to see how it is done."

Mercy, an advocate for the rights of persons living with disability, knows the difference between inclusion and exclusion because she wasn't born with a disability. Growing up in a close-knit family in Meru County, she spent her days with her brothers whose activities she found more exciting.

"I have sisters but I loved being with my brothers. We climbed trees, slid down muddy slopes, collected firewood, cut napier grass for the cows... I loved it!"

Although Mercy couldn't do as much as the boys because they were bigger, she enjoyed the sense of participation. Looking back, she believes the 'rough' games could have caused an illness that led to her present disability.

"I wore dresses, which weren't very conducive to the rough games we played. I often went home with bruises on my legs from sliding down branches. My brothers had no such problems because they wore trousers," Mercy says.

One day, when she was 10, she mentioned to her mother that her left leg was aching. Her mother was preparing to travel out of town and thought Mercy was just seeking attention. "She rubbed some ointment on my leg and assured me I would be fine," recalls Mercy, who works in communications with a leading corporate organisation.

Where it begun

Walking home from school at lunch time the same day, her legs gave way and she sat down on the roadside about 200 metres from the school gate. Her brothers, who were entrusted with caring for her whenever their mother was away, thought she was being her usual playful self.

"They were rushing home to prepare my lunch so they could get back to school. They thought I was fooling around because I wanted to be carried all the way home. They told me those games were for after school and left me sitting there, convinced I would get up and follow them. But my legs would not carry my weight."

Then a close friend and neighbour passed by and asked Mercy why she was sitting there. "Thankfully, Mugambi took me seriously and carried me home," says Mercy. "My brothers thought I had duped him but he convinced them I was unwell."

By the evening of July 26, 1994, Mercy's left leg was swollen. The next day, her father carried her to hospital and over the next three months she had several tests and lots of medication. On being discharged, she was using crutches.

"All of a sudden, life changed from unrestricted movement to this," she says. "The focus changed for the whole family. Everything became about ensuring I was comfortable and had my medication."

If Mercy felt fine, she was allowed to go to school but she wasn't supposed to wake up early; if not, she stayed home. In school, she could not play and discipline no longer included a beating.

Although this was done in her best interests, no one thought to explain to Mercy what was happening. "I didn't understand why I was suddenly this special child being excluded from 'normal' activities," she says, adding that she was finally diagnosed with osteomyelitis, an inflammation of the bone or bone marrow usually due to infection.

"I sought inclusion based on my earlier carefree life and as a result I am often described as aggressive," she recalls. "I was in and out of hospital between Standard Four and Standard Seven and this disruption made me feel like I was missing out. So I decided to take 'revenge' by becoming extra studious – I ensured I came first in class throughout."

Mercy recalls a life governed by antibiotics and weekly hospital appointments as her left leg gradually stiffened until she could no longer bend it. When a friend took her to Kenyatta National Hospital in Nairobi, it was discovered that the leg was also longer than the other by about 5cm – that was when medical experts recommended that she should start wearing modified shoes.

"By this time I was a Standard 8 adolescent and conscious of my looks. I hated the boots on sight and I hated my father for not understanding me. I cried and refused to wear them," says Mercy. "Looking back, I realise how much I tormented him yet he was doing everything he could for me."

Once again lacking counselling about this new twist, Mercy spent the next day crying. It got so bad that her father issued an ultimatum – if she refused to wear the shoes then she could not go to school. As she wondered what was happening to her world, a schoolmate came to visit.

"He was a good friend and he came to find out why I was not at school," she says. "In no time he had talked me into wearing the shoes by offering some much-needed words of affirmation. I was sold."

Since then, Mercy has learnt that she need not restrict herself to black boots. On the day of our interview, she is wearing feminine sandals, one of which is raised to obtain equal height in both legs.

Mercy says her friend encouraged her to return to school wearing the shoes and took it upon himself to protect her from cruel school mates. But the most precious gift he gave her was a feeling of usefulness.

"He gave me a role (albeit small). I was in charge of keeping his locker key while he played sports. This was so different from home where I was excluded from even the smallest chores. I know this was out of love and concern but it reminded me that I was sick."

It was a dark, lonely time for Mercy – while her peers were giggling about girly stuff, her condition caused her mother depression, which pushed her to seek divine intervention. "We tried everything, including dipping myself seven times in a local river (like the Biblical character Naaman) in the hope of finding healing," she says.

"I remember crying bitterly when the seventh dipping brought no change. It was at that point that I began to bargain with God – take the pain away and give me enough health to use my condition to help others."

Mercy, whose self-esteem was very low at this point (she could not even look at herself in the mirror), got busy in church doing everything that needed to be done – it was all about the need to feel useful.

Going to boarding school for Form One was a huge issue for the family. She was admitted in St Mary's Egoji but her father had serious reservations about letting his 'fragile' child go. Only the fact that she had cousins attending the same school made him soften his stand – but with conditions. "For instance, I was not allowed to do my own laundry," she says. "Even today when I go home, I am stopped from doing any chores," she says.

Experiences

In boarding school, she made friends with three other students with disability and they remain friends to this day – simply because they could share experiences. However, there were challenges. "Games time was torture," says Mercy. "The games teacher had no clue how to handle disability and fully expected us to participate like the other students. It was cruel."

At Kenyatta University, where she was a student from 2005-2009, there were over 50 students with disability. Feeling a strong need to tell people how to treat her and others like her, Mercy became the congresswoman for students with disabilities.

And as a member of Kenyatta University Students Association, she wrote proposals to the Senate and influenced policies regarding students with disability. She also advocated for the institution of a Disability Directorate Office, which was implemented in 2010.

Towards graduation, Mercy registered Ability Society of Kenya (ASOK), which mentors children with disabilities to become academic achievers and also secures jobs for persons with disabilities. ASOK also trains job applicants how to write CVs and prepare for job interviews with help from Africa Talent Bank, one of its partners.

"ASOK writes to companies to employ persons with disability with a reminder of the Disability Act's 5 per cent employment requirement," says Mercy, adding that her nomination to the Women in the Red Leadership Awards in October came from beneficiaries of her efforts to get them employed.

"Disability is not the issue," she says. "It is lack of correct information and empowerment. Disability awareness is my life because I believe it will eliminate discrimination," she concludes.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.