Moments after the declaration by the IEBC chairman that Deputy President William Ruto and his running mate Rigathi Gachagua had won the presidential election, Kenyans had already baptised their new leaders.

Ruto, who was no stranger to the nicknames doled out via social media, was branded 'Kenchic 1'. Not long ago, his opponents referred to him as 'Tangatanga'. By the time Kenyans were going to the poll, he was most readily known as the Chief Hustler.

Gachagua, meanwhile-a man social media had been raking over the coals since it was revealed he would be the second-in-command-was christened 'Riggy G'.

Kenyans had been joking about the elections for months. In the weeks leading up to it, the jokes ramped up online, and as they held their breath waiting for the results to be announced, humour seemed to be an easy balm for most.

It was the same social media that once referred to the late President Mwai Kibaki as 'Big Daddy Baks' or 'Obako'; the same people who couldn't remember Wangari Maathai's name and simply rounded it up to 'The shawry for trees', and the ones who saw their President as a 'Jayden' or 'Kamwana', eventually forcing Uhuru Kenyatta out of social media platforms.

Nobody was safe from the banter of young, creative Kenyans, it seemed, not even the man occupying the highest office in the land.

"My favourite thing about the period was the memes," says Mike Kirui, a Communications student. "We love to make fun of serious situations, and the elections were no exception. It's a great thing, not just because laughing about it makes it easier to deal with, but also because it shows nobody is above criticism or being laughed at."

IEBC statistics show that the share of young people among the 22.1 million who registered to vote dropped by 5.27 per cent compared to 2017.

- Community health workers boost counties universal healthcare bid

- Inside UON's digital health facility

- Cabinet okays NHIF scrapping if four bills get MPs nod

- Ruto reaffirms State's support for health sector under devolution

Keep Reading

Indeed, young people's contribution to the democratic process will mostly be remembered in the form of the jokes they made, at every stage. From the young man telling a reporter "Sina maoni" at 6am, to the sly comments about Chebukati's undoubtedly superior hair oil, all the way to the arithmetic banter following the 0.01% saga. If there was humour to be found in anything, those young people on social media dug it up and shared it.

It was the best they could do, a lot of them now say. They could not be bothered to vote, for one. Not when the choices were so uninspiring, and not in the wake of an increasingly dire economic situation that had left them disillusioned with their leaders.

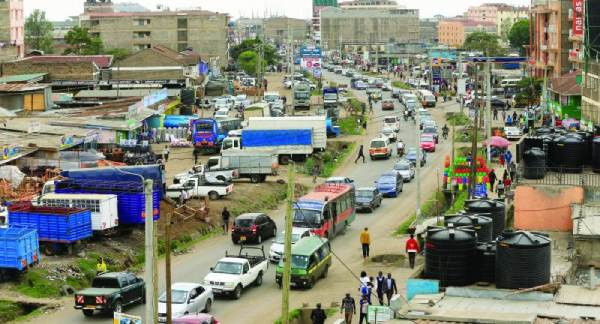

"I think a lot of us feel like this election doesn't change anything for us," says Nickson Chemei, a young man who owns a shoe business in Nairobi. "In my case, I have been struggling to keep my business open this past year. First there was Covid, which was a major challenge. And then the period afterwards was just as difficult. I cannot even think about who is running for what. In a month, it won't matter to my business."

"I did not have a relative vying," is Sophie Adhiambo's reason for not voting. Nothing else would compel her to make the trip back home, to the polling station in the village from where she has never bothered to switch her registration. So she stayed home, and the next day, showed up to work as usual.

"It's not like my vote counts," she adds. "For so long now, every election has had accusations of fraud and stealing. I know my vote does not matter, because they rig it for whoever the system is aligned to."

Does she care that not voting means letting other people decide something that will affect the whole country?

"Not voting is also a form of protest," she insists. "It is like ticking 'None of the above' on the ballot, because realistically, none of the options presented to us felt like a good choice. People talk about young people's apathy, but they should be focusing on the lack of better quality in leaders."

And so most young people abstained from the democratic process, choosing instead to look in from the outside, only popping in to make fun of Riggy G's dressing, to throw a barb at Tanzanians when they started laughing at our national arithmetic ability, and to say "I told you so."

"Look at the shenanigans going on right now," Chemei says. "Three weeks later, and we still don't know for sure who is going to be president. More importantly, politicians are already switching sides and aligning themselves for the future. You can't convince us that these people care about the country or even young people."

Can't relate

"Young people feel used or misused by politicians," explains Javas Bigambo, a governance expert, lawyer and political analyst.

"The perceived social contract between the leaders and the people does not appear to bear any fruit once these people get into office. They do not honour manifestos or promises, they are very elusive once they get into office, and in the next elections, they come with the same promises."

"Additionally, older leaders have no mechanism for engaging young leaders.

Raila Odinga comes to a rally and talks about how he fought for multipartism and how he was jailed for it. He talks about the fight for freedom of expression. These are things young people do not understand. They were born in a world where multipartism and freedom of expression are natural things. They cannot relate to the agenda."

"When Kalonzo Musyoka says, 'We cannot surrender our country to thieves'... there are young people who are not employed and are forced to resort to thieving to feed themselves."

"No one is engaging with them intellectually, so why should they bother to register or vote? We need to have a rethink of the political framework in a way that the interests of the young people are given attention."

The tendency of young people to use social media to make fun of or banter their leaders, Mr Bigambo points out, is another indicator of social evolution.

"Social media represents a new platform and a new opportunity. It is a function of technology and creativity. Creating memes of politicians in the way young people are doing is a way to centre their creativity and artistic skills. Most of them don't see it as offensive. They don't see it as insulting a leader. For them, it is an expression of their artistic self. Leaders should get out of the mindset that someone is abusing them and find ways to make use of this creativity to bring about the greater good."

We must consider, also, that the reasons for getting into politics are different for these generations.

Older politicians were mostly looking at politics as a way of protecting interests or preserving wealth. Younger generations have different priorities. They have no wealth. They want to create opportunities for themselves, to better their situation."

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and international interest.