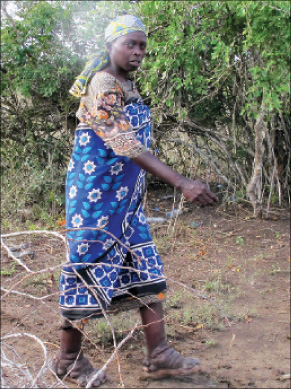

Christine Sani of Kilifi County suffer from elephantiasis. The disease has affected many people in the area.

Christine Sani of Kilifi County suffer from elephantiasis. The disease has affected many people in the area.

By PAUL WAFULA

KILIFI, KENYA: Pekeshe Kadenge has been concealing some weight around his private parts using a leso for the past 18 years.

The private nature of his condition made it difficult to seek medical attention in public hospitals. But he had no choice after his legs began swelling.

Kadenge, 75, is a resident of Mbararani village in Kilifi County. He suffers from a condition that is most endemic at the Kenyan coast; elephantiasis.

Elephantiasis affects thousands of people in Kilifi yet it can be prevented. The disease has no cure and access to treatment is often hampered by stigma and poor health infrastructure.

The most visible part of the disease is the swollen legs, but there are cases like that of Kadenge, where people suffer from swelling of the legs and private parts.

Because of his condition, Kadenge does not wear trousers. They can be uncomfortable, so he prefers the coastal style of tying a leso around his waist.

“This is my 18th year with the disease. I cannot go on a long trip. I cannot walk for long distances. In the last three months, I haven’t left my compound,” Kadenge reveals.

His condition has worsened in the last two years after both his legs began swelling.

“My wife fends for my children. She brings me food here on this mat. Sometimes I shiver and drink a lot of water and lose my appetite for food,” he adds.

Kadenge directed us to the homes of two other people with the same condition. In a neighbouring village, we meet Christine Sani, 23, who dropped out of school more than a decade ago after she got the disease.

Sani has to lift an extra 10kg of weight as she walks around. She rejected attempts to have her legs amputated. She would rather keep them in that form than walk around on crutches, she reasons.

TROPICAL DISEASE

In the next village, named Forodhoyo, lives Dhahabu Kenga, 47. She stopped attending clinics when doctors were no longer available to attend to her.

“Every time I went to the clinic in Kilifi, I was told the senior doctor who would attend to me was unavailable. So after three months of no treatment, I stopped going,” Kenga tells us.

There are more cases, which we find without much effort in Kilifi County’s Ganze Constituency.

But these three best illustrate the pain of thousands of residents who are silently suffering from elephantiasis in Kilifi County, which is one of the six most neglected tropical diseases in Kenya.

Ironically, the Kilifi county government is yet to prioritise elephantiasis in its budget.

“There is an issue with elephantiasis, mostly in Kwale. I must say it is being handled like any other disease in terms of curative and management measures,” Kilifi County’s Executive Member for Health Swabah Omar told The Standard.

Her office has commissioned a study that is being conducted by Kenya Medical Research Institute to inform action. This is despite the existence of numerous studies done by both Government and international agencies on the disease.

An ambitious five-year strategic plan for the control of neglected tropical diseases was released by the Ministry of Health. It maps out where the disease is most prevalent, while giving recommendations on what should be done to meet the international goal of eradicating elephantiasis by 2020.

The strategic plan was commissioned by the then Public Health minister, Beth Mugo, and was to be implemented between 2011 and 2015. That has not happened.

Locally, Kilifi County has not budgeted a single cent towards fighting elephantiasis in its over Sh300 million health development budget for 2013/2014.

Kilifi will invest Sh255 per person to develop health services. This is six times less than what Lamu County has set aside to spend on each resident.

HIGHEST SPENDER

Lamu will invest Sh1,659, making it the highest spender in the Coast region. It is followed by Mombasa at Sh498 per person and Taita Taveta at Sh449. Lamu is the second biggest health spender per person in all the 47 counties, coming after Kisii County.

If you live in Kwale County, your county government will spend Sh263 on developing healthcare services while Tana River plans to invest a shilling less than Kwale, making it the fifth in the six counties at the Coast. These figures are limited to development expenditure on health only.

We divided the planned development health expenditure by the 2013 population sizes in each of the counties to get the amount of money each county will spend per person.

In addition to being the lowest spender, Kilifi has also been shrinking its health budget at a time when it has pressing health needs. Dr Omar reveals that her docket had initially sought Sh2.6 billion for health. Only Sh1.5 billion was approved.

“The budget came back again for further action and it was reduced to Sh1.4 billion. So this is our working budget at the moment. We have allocated Sh400 million for development and Sh1 billion for recurrent,” Omar says.

According to its strategic plan, Kilifi County needs at least three paediatricians to complement the existing one. It also needs a similar number of anaesthetists and physicians.

DEADLINE

“We have only one anaesthesiologist who is fully qualified in the whole county. He has been working for the last four years without leave,” Omar adds.

The plan, part of which was shared with The Standard, shows that the county has a shortage in virtually all staff cadres offering public health services.

The county also has a gap of six surgeons, five ophthalmologists and is in dire need of 1,250 medical officers. It currently has 50 medical officers and has no ophthalmologist.

It also needs four more radiologists and hundreds of clinical officers to effectively serve its population.

The county’s health secretary also admitted that the budgeting process was done in a hurry to meet deadline, and it did not factor in the various health needs in the final determination on how much is allocated for health development.

“We attended a two-day workshop to make the budget, which I believe was not enough,” Omar says.

“The best thing would be to look at the demands within the county and allocate appropriately for each activity,” she adds.

HEALTH OUTCOMES

The figures of what counties will spend on health per person were calculated using data contained in a Commission of Revenue Allocation (CRA) booklet presented to the Inter-Governmental Budget and Economic Council Meeting of August 12, 2013.

The analysis was limited to development expenditure because this is where all counties had a free hand to determine what to spend depending on their priorities.

Also, development expenditure is the best indicator of how counties have prioritised health. It is also the best available tool for forecasting if residents should expect better health outcomes.

The CRA booklet also contains a breakdown of intergovernmental transfers by county, revenue generated at county level and expenditure estimates.

“An aggregation of county budgets shows that 69 per cent of revenues will come from national government transfers while 31 per cent will be generated from own revenue sources,” CRA chairman Micah Cheserem says in the report.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.