When Risper Shirin experienced menarche - the first menstrual period in a woman - in 2015, she was overjoyed at "becoming a woman", a pride that many girls her age at that time bubbled with as they transitioned from childhood to adolescence.

But little did she know that period poverty could blight her bliss. "It was a fine day amid the jubilant atmosphere of receiving our KCPE results, I sensed some dampness in my panty. Out of curiosity, I rushed to the bathroom to check what was happening," she confesses.

"To my shock, I found out that my underwear was soaked in blood. The realisation that I had begun menstruating struck me, a natural process that I had little knowledge about, but never thought it would come that day," she adds.

"Mixed emotions swirled within me, and I was unsure of whether to cry or smile at the onset of womanhood," says Risper, a third-year journalism student at Rongo University.

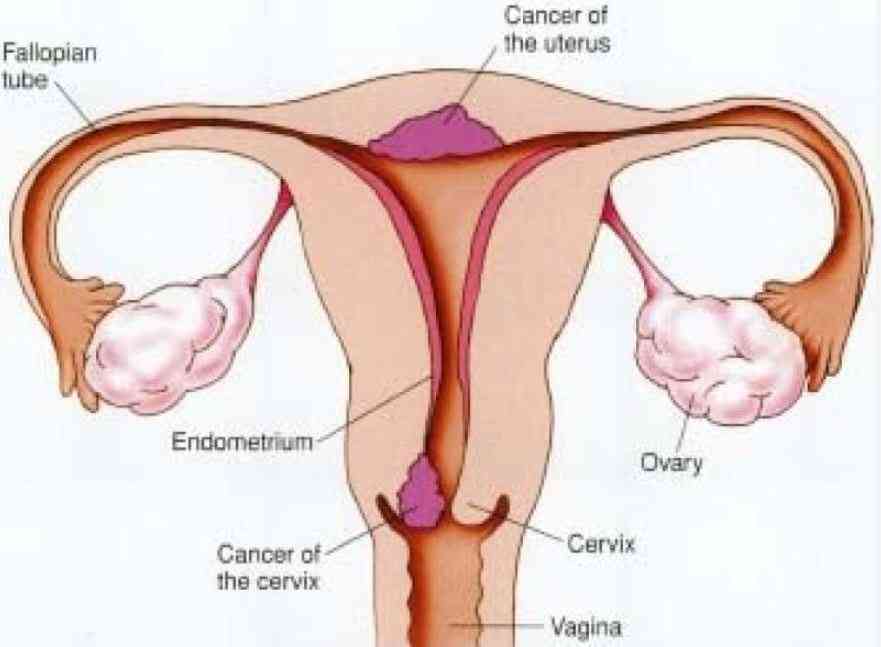

According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), menstruation is the process in which the uterus sheds blood and tissue through the vagina. This natural process occurs in females of reproductive age. It is a healthy part of life for most women and girls. Globally, 800 million girls menstruate daily.

It begins on the first day of menstruation accompanied by the uterus shedding its lining through the vagina which takes 1 to 5 days. During this phase, oestrogen and progesterone levels drop to trigger shedding of the uterine lining, resulting in menstrual bleeding.

For Risper, poverty in her home could not give her a chance to enjoy the onset of womanhood. Despite her joy at being normal, the struggle with period poverty made her regret being born a girl.

"When it dawned on me that this will be a normal occurrence every month, I always felt disheartened due to pervasive poverty at our home, which denied me a chance to taste the feeling of using pads during menstruation," she confesses.

"Being the firstborn has a great impact on many girls, making them view what ought to be a natural transition as a burden," she adds.

According to UNICEF, every month, 1.8 billion women menstruate globally. Millions of them are unable to manage their menstrual cycle in a dignified and healthy manner.

In Kenya, data shows that 65 per cent of women lack access to menstrual products, with one million girls missing school each month because they cannot afford sanitary pads while some share used ones.

This data resonates with a survey done by Proctor and Gamble and Heart Education, which found that 42 per cent of Kenyan school girls have never used sanitary towels, thus resorting to alternatives such as rags, blankets, pieces of mattress, tissue papers and cotton wool. Risper fell in this category.

"Due to period poverty, I had to manage my menses with rags. It was not a big deal at home and my mum could help me cut unused clothes into small pieces after which I could use them during my periods. Later on, I got used to them and I was just comfortable," Risper admits.

"However, the issue worsened when I joined high school. I was used to rags to manage my menses but in high school is when realized most girls were using sanitary towels. This was my worst experience ever especially considering that I was in a boarding school and many times I was discriminated against for using rags. I wished I was in a day school and missed school when on my periods. But it was impossible because I was being sponsored," she narrates.

Risper also explains that her poor state saw her struggle with a shortage of panties. This often convoluted her menses. "Apart from lacking pads, I also didn't have enough underwear. I remember in Form Two in term two, I only had three panties. Unfortunately, one was stolen so I had to survive with only two for the whole term. This made my menstruation tougher, especially with limited water in school," she remembers.

"Using rags poses a great risk and can cause infections especially if not cleaned up properly. It is important to clean them well before use and replace them often," says Dr Saudah Farooqui, an obstetrician-gynaecologist at the Nairobi West Hospital.

Risper also elaborates that relying on rags often caused her to miss class time because she had to frequently go to the toilet to check, to prevent leakage and potential stigmatization from her classmates.

Additionally, she notes that inadequate water at her school prevented her from keeping the rags clean as necessary, yet she persevered despite these challenges.

According to the World Bank, an estimated 500 million women still lack adequate facilities for Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM). Inadequate Water, Sanitation and Hygiene facilities particularly in public places can pose a major challenge to women and girls.

"I believe there is a lot we can do to end period poverty, but creating awareness at the grassroots level on its consequences is very important. Let's have other options that can help girls with the same problem so that they don't regret why they were born girls," she says.

She advises girls to embrace those grappling with period poverty and help them in case of need and avoid stigmatising them. She also urges them to share with those who may not afford to buy sanitary towels to end stigma.

"Period stigma is worse and can leave you with scars that can take time to heal. Nobody wishes to use rags or any other thing to manage their menstruation. Sometimes the stigma can leave you battling with mental issues and self-hatred that can lead to self-harm if not addressed," she says.

Risper notes that the government through the Ministry of Health has greater responsibility of ensuring all girls access sanitary towels.

"To end period poverty, outreach programs are necessary to ensure that all people are well informed on its effects and collective responsibilities are upheld to ensure girls struggling with period poverty are supported. This awareness should be trumpeted in all forums. In addition, the government should remove taxes from menstrual products and set aside funds to avail and distribute them in impoverished areas," Dr Farooqui explains.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.