Audio By Vocalize

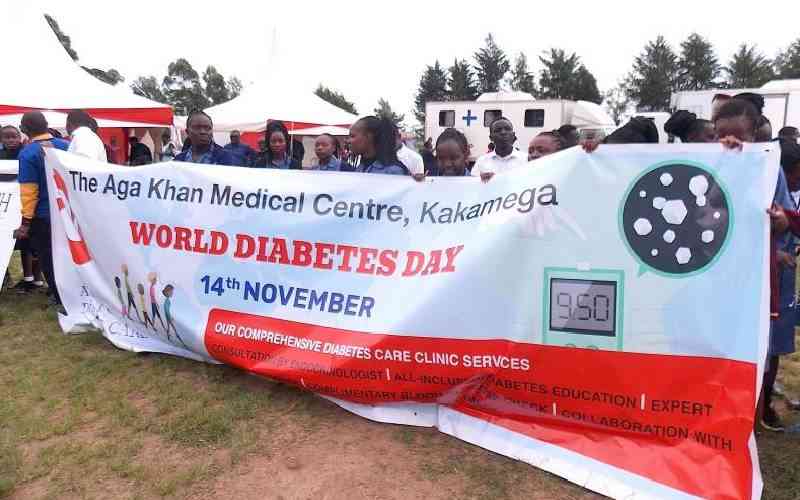

Participants during World Diabetes Day organised by Kakamega County Department of Health at Approved School of Kakamega, on November 14, 2023. [File, Standard]

When 24-year-old diabetes advocate Precila Ngipuo wrapped her arms around a tree in Lodwar, Turkana Central, she was not chasing attention. She was chasing survival, for herself and for thousands of poor diabetes patients whose daily lives are shaped by the high cost of medication, poor nutrition and constant vigilance.

Less than ten hours later, she was lying on a hospital bed at Lodwar County Referral Hospital, weak, dehydrated, and connected to a drip. Her protest ended early, but the conversation she sparked has only just begun.

“I knew it would be hard,” Ngipuo says quietly. “But I didn’t expect my body to shut down that fast.”

Ngipuo was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes in 2022, when she was in her early 20s. “People think Type 2 diabetes is for old people,” she explains. “But even young people like me are suffering.”

Addressing assumptions about her appearance, she adds, “People see me now and think I was always small. But before I was diagnosed, I had weight. The sickness is what reduced me.”

Managing diabetes is not only a personal battle but a family responsibility. “I am a single mother of two children,” she says. “When I fall sick, my children are affected immediately. If I don’t survive, they suffer. So this struggle is not just about me. It is about them too.”

Medicine is expensive. Special food is expensive. Even transport to hospital is a challenge. “Sometimes you have insulin but no food. Sometimes you have food but no insulin,” she says.

“Diabetes does not take a break,” she adds. “You wake up with it, you sleep with it.”

The protest ,hugging a tree for 72 hours , was symbolic, a silent call for attention to the plight of diabetes patients, especially those who cannot afford proper care.

“I wanted people to feel uncomfortable,” Ngipuo explains. “If my body is uncomfortable every day because of diabetes, then the country should also feel uncomfortable knowing patients are suffering.”

She emphasises that her protest was not about heroism but desperation. “People talk about diabetes like it is a small disease. But people are dying quietly. I wanted to show that this is serious.”

Ngipuo did not take her diabetes medication during the protest. “I knew if I took insulin and did not eat properly, I could collapse faster,” she says.

Doctors later confirmed that skipping medication significantly worsened her condition. Extreme physical actions, prolonged heat exposure, dehydration, and missed meals can quickly become life-threatening.

“The body is already fighting a daily battle,” one clinician said. “Protest should never cost you your life.”

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

Ngipuo says the first few hours were manageable, though exhausting. “The sun was hot. I felt dizzy, but I told myself to stay strong,” she recalls.

As hours passed, her energy drained rapidly. “My hands started shaking. I felt very weak. My head was spinning,” she says. By the ninth hour, she could no longer stand properly. Witnesses alerted health officials, prompting an emergency response.

“I didn’t want to be taken away,” she admits. “But my body had already made the decision.”

At hospital, doctors stabilised her condition with fluids and close monitoring. Hospital CEO Nancy Kinyonge later urged the public, especially those with chronic illnesses, to put their health first.

Now recovering, Ngipuo does not encourage other diabetes patients to copy her protest method. “I wanted to make a point, but I don’t want anyone else to risk their life like I did,” she says.

“There are many ways to speak out — through media, petitions, dialogue. Our bodies are already fighting a daily battle,” she adds.

Despite the early hospitalisation, her protest succeeded in amplifying the conversation around diabetes care. Residents who followed the event were moved by her courage.

“She could not finish the 72 hours, but even those hours were powerful,” said Samuel Leme, a local teacher. “It showed how serious this issue is.”

“This is what we face every day,” said Mariam Atieno, a 35-year-old mother living with diabetes.

“If even young, strong people collapse, imagine those of us struggling quietly.” Another patient, Joseph Ouma, 28, added: “It’s not about heroism. It’s about survival. Her protest reminds us that health always comes first.” Ngipuo hopes policymakers will listen, particularly on the inclusion of diabetes medication among essential drugs. “I did not hug that tree for nothing. I want change,” she says.

Her protest may have ended under a hospital roof, but her message stands rooted, like the tree she held onto, in the urgent need for affordable and accessible diabetes care.

Ngipuo’s experience highlights broader systemic issues: access to insulin, nutrition, and health education remains a daily challenge for many people living with diabetes.

“Sometimes it feels like we are invisible,” she says. “The cost of survival is not just money — it is time, it is energy, it is risk.”

Experts say her story serves as both a warning and a lesson for young diabetes patients.

Dr Angela Muthoni, an endocrinologist in Turkana, explains: “Extreme physical stress combined with missed medication can trigger diabetic emergencies within hours. Patients must prioritise their health over protest or public demonstration.”

For Ngipuo, the protest was never about heroism but desperation. “I did not do this because I wanted attention,” she says. “I did it because the system is failing people like us , patients and families who depend on us.”

Her call is simple but urgent: advocacy must not come at the cost of life. “We deserve to live,” she says. “And while we fight for better care, we must also protect ourselves. That is the first protest we can make.”