×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

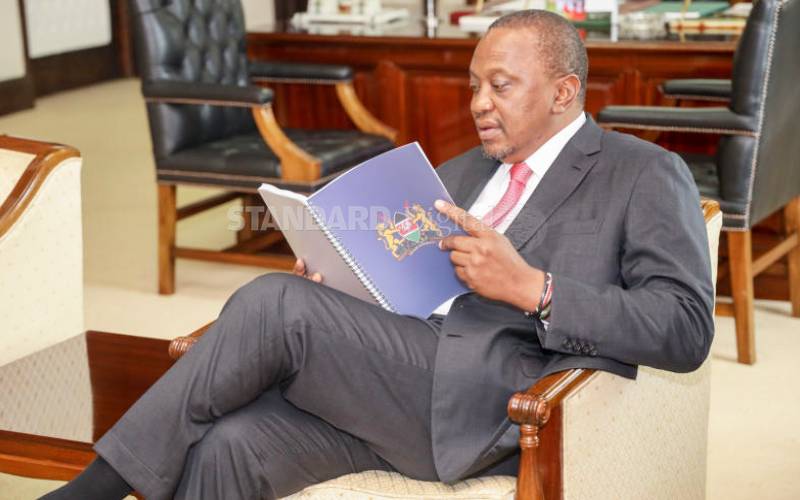

President Uhuru Kenyatta reads through the Building Bridges Initiative report when he received it at State House, Nairobi.

“Why are they taking that stuff away,” asked a friend in utter indignation.