×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

A cousin of President Uhuru Kenyatta won back his inheritance after a protracted legal battle that culminated at the Court of Appeal earlier this month.

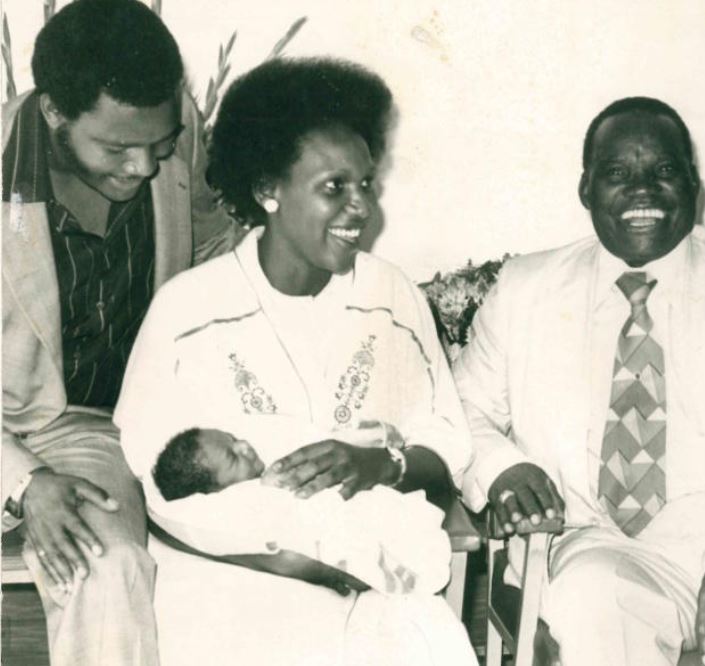

Peter Mugo, born to Elizabeth Mumbi and Jomo Kenyatta’s brother James Ngengi Muigai, had been left out of his father’s will. Also left out was his brother Peter Nyoike.