After more than two decades of playing host to the world’s largest refugee camp, a once accommodating government has had enough. In April, Deputy President William Ruto said the camp should be shut down and its more than 350,000 inhabitants repatriated to Somalia.

Peace still seems elusive in Somalia, and its absence has over the years been reason enough to allow for the different facets of Dadaab refugee camp to thrive.

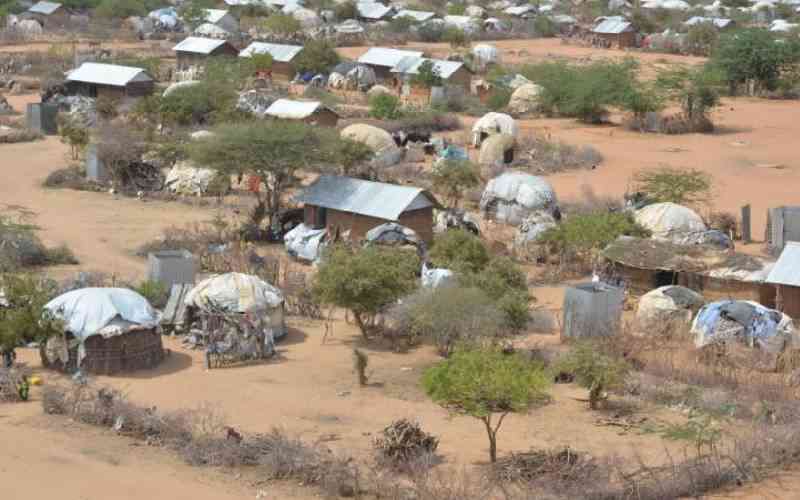

The Dadaab refugee complex in northern Kenya is a cramped affair smack in the middle of a dust bowl that, in the blink of an eye, can turn into a flood plain. Originally designed to accommodate 90,000 refugees, the camps now hold four times that number. This makes Dadaab the third-largest population centre in Kenya after Nairobi and Mombasa.

From an outsider’s perspective, Dadaab’s remoteness and harshness have conspired to make it, like the rest of the former North Eastern Province, almost uninhabitable. Areas around the refugee camps are often run by groups of armed, merciless bandits who have preyed on the desperation of the refugees, the goodwill of the locals and the absence of a functional government.

But for the insiders, Dadaab is home, with challenges like any other ‘town’. “The Government should ask itself why it is not hard for a young man to say ‘no’ to Al Shabaab advances,” Mohamed Abdi, the youth chairman at Dagahaley Camp, says.

“Look at it this way, I was born at the camp. I went to school here and completed my secondary school education. Then my world came to an abrupt end. Even with my high school qualification, I cannot get out of Dagahaley in pursuit of a better life. Effectively, I am retired at 20, without ever having worked.”

He and many of his age mates know no other country but Kenya, “But we are treated like second class human beings. I cannot even go to the nearest town without special permission from the Department of Refugee Affairs. Tell me how we will convince our friends that Al Shabaab is the enemy yet they are offering free movement and want to utilise what we learnt in school.”

Official data from the Department of Refugee Affairs shows there are more than 6,000 grandchildren of the original 1991 refugees born in Dadaab. Like many of their parents, these children have never seen Somalia and are practically aid dependent guests in overcrowded shelters.

It is almost impossible to think that things could get worse for this group. Among them live members of Al Shabaab, who use the remoteness of the outpost and alleged greed among police officers deployed in the area to thrive and move freely.

“Al Shabaab will demand quasi-religious loyalty. The corrupt police will demand their cut or else they will brand you a terrorist. If you try to escape all this, you become an illegal alien and can be jailed,” Muhamed Salat, 31, says.

Salat and some of his friends try to keep themselves occupied. Through donor funding, in 2005, they set up a computer and ICT centre, where they teach school leavers basic computer skills. After each class graduates, instructors are asked the same question: We now know about computers; what next?

The international community has argued that the Kenyan Government is using Dadaab as a scapegoat in its war on terror.

On April 2, the country woke up to the troubling news of a siege in Garissa, the closest urban centre to Dadaab. By dusk, 148 students and security personnel lay dead. Less than 24 hours after the siege, Al Shabaab claimed responsibility. The Garissa massacre rekindled talk of closure of the camps.

Investigations by The Standard on Sunday indicated that the attackers did not have to go through Dadaab to get to the university. Security sources told The Standard on Sunday that the attackers used Fafi Road, a seldom manned road that starts at Kenya’s border with Somalia, through Wajir South and stops barely 50 metres from the university’s gate.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

In effect, Fafi Road is the designated smuggling route for both goods and human beings.

Chiefs at the different refugee camps, who did not want to be named for fear of reprisals, said they provide intelligence to relevant authorities but the information is seldom acted upon. Instead, whenever suspicious individuals are spotted in the camps, some in law enforcement are accused of seeing this as a path to riches.

For instance, on March 26, 2013, two customs official were gunned down in Garissa Town. Local authorities blamed the killings on robbers.

Illegal entry

But other residents claim the customs officials, after learning of the illegal entry of contraband courtesy of individuals sponsored by a local businessman, extorted money from the trader. After getting their cut, they then told their colleagues of the windfall, and they went to the same businessman for cuts of their own. Fed up, the traders ordered a hit and less than 24 hours after the deal, the two lay dead side by side.

“We agree that terrorists may be hiding among refugees. But we are also sure that greed among our security agents has played a big part in this mess,” security expert Ng’etich Bitok told The Standard on Sunday.

Multiple interviews with security agents in the region also point to sellouts within the force. There have been reports of team leaders claiming urgent off days and feigning sickness hours before deadly missions.

“In essence, we are shooting ourselves in the foot. For us to be successful, we will need the refugees on our side,” Ng’etich says. “We will need to treat them humanely.”

For Ahmed Muktar, also a founding member of the Dagahaley ICT centre, this will include some freedom of movement. It is three years since he stepped out of the camp.

“Unless you have a very good reason for getting out or have a heavy pocket, you will not leave this place. Now you know why the wrong people are making their way into Kenya. The law abiding continue to suffer,” says Muktar.

His colleague, Salat, first left the camp in 2003. Back then, movement was not very restricted. He managed to get a permit to go ask for a school uniform from his uncle. Three years later, he left the camp again, then one more time in 2013. Three times in his lifetime.

“At least 100,000 of us are young people with a proper education. If you forcefully send us all back to a country we do not know, where will most of us end up? There are no jobs in Somalia. There are no opportunities. Some of us have no family on the other side of the border. Many of us will end up taking up arms,” says Salat.

If they ever went back to Somalia, Salat and Muktar would be called Somali siju - derogatory term for outsider. In Kenya, they are aliens.

Does Muktar think that one day he, too, will be considered Kenyan? “I don’t think so. But if it happens, we will contribute a lot to the country in our own little way.”

Going back to Somalia might be easier for Abdi Walid Shiriye. He has been at Ifo 2 camp for just three years. He, unlike Muktar and Salat, has 43 years’ worth of memories of his homeland. But still, he says it will not be easy for him to make that return trip. Fighting between Al Shabaab and government forces in 2012 resulted in massive destruction in his village.

“I am a pastoralist. All my animals died in that conflict. Yes, if Kenya gets tired of me, I will go. To what, I don’t know,” Shiriye says.

For now though, he stays his welcome. Every day, more trickle into the camps officially or unofficially in search of a better life despite of the impending camp shut down.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.