By Jevans Nyabiage and Emmanuel Were

Kenya: For a majority of Kenyans, a conversation on spending within their means, increasing their productivity at work, borrowing wisely and investing prudently makes for a very uncomfortable talk full of hard facts.

Most individuals would rather chit chat about how well, or badly, so and so is doing, or what car they want to buy next, or the country’s politics. And in these kinds of discussions, hard facts are not allowed to get in the way of a good tale.

This aversion to facts, however, appears to have reached a national scale.

The state of Kenya’s finances is debated emotionally, rather than rationally and on substantive figures and policy direction.

This is mainly because politicians often lead the discussion on pay rises, wage cuts, development projects and taxation. This mostly leads to populist statements that resonate well with the masses but are not necessarily prudent for the country in the long run.

But in the coming months, there will be no escaping tough debate on the state of the country’s finances.

Already, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund have raised the red flag on the uncontrolled jump in both the public wage bill and debt.

The IMF’s and World Bank’s concerns could not have come at a worse time as Kenya is about to issue a sovereign bond to raise Sh130 billion ($1.5 billion) from international lenders.

But borrowing in dollars, like the country would with the bond, poses a risk because the loan has to be repaid in dollars, yet Government revenues are in shillings.

If the shilling weakens further from the current Sh86 to the dollar and heads to Sh90 as estimated by some analysts, the country would have to work hard extra hard to repay the debt. Kenya would have to rely on foreign-exchange earners like tourism, coffee, tea and horticulture.

Warning

And with the joint IMF-World Bank note to organs that determine lending rates, Kenya’s chances of getting cash at low interest are compromised as the warning has essentially told these institutions to be wary of the country’s ability to repay the cash it borrows.

The exact date the sovereign bond will be issued has been a moving target. Initially, it was supposed to go ahead late last year. Then it was pushed to the first quarter of 2014. Now, the date is in limbo.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

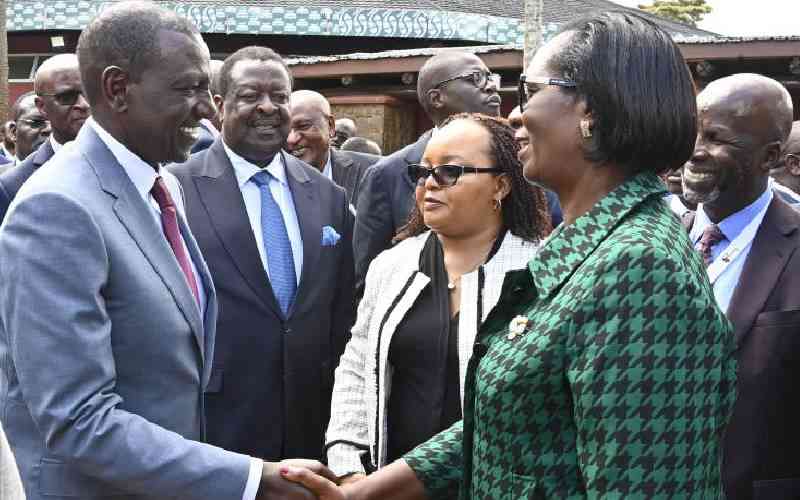

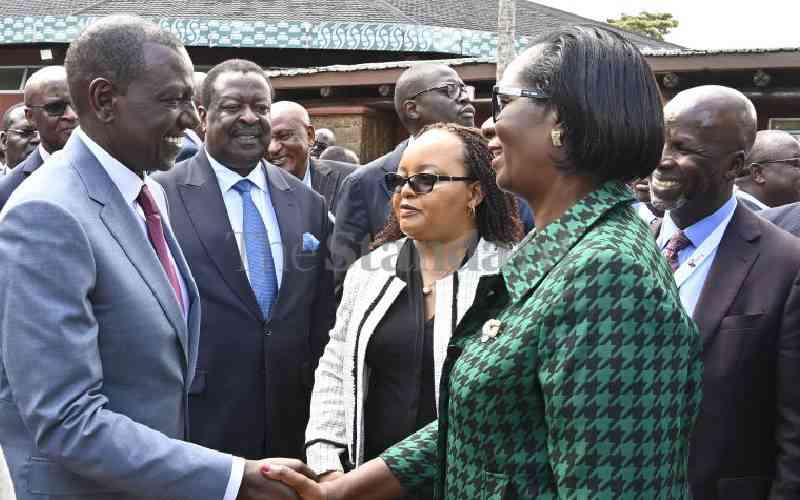

What is known is that the wage bill has to be trimmed. This is why President Uhuru Kenyatta and Deputy President William Ruto have been quick to take a 20 per cent pay cut. President Kenyatta also directed ministers and parastatal chiefs to follow suit.

Kenya’s wage bill stands at 12 per cent of Gross Domestic Product. This compares what the country pays in wages to what it produces. The global best practice is for wages to not exceed 7 per cent of GDP.

But the public wage bill is only one side of the coin.

Kenya is staring at another crisis: its debt. The amount of money the country has borrowed will reach Sh2.2 trillion by June 2014, according to the National Treasury.

At this level, Kenya’s debt to GDP level will be about 54 per cent.

This comparison of debt to GDP is important as it compares what Kenya owes to what it produces. Many analysts use this ratio to measure the ability a country has to pay back the money it has borrowed.

This is quite similar to how a bank evaluates an individual’s ability make his or her monthly loan repayments based on the salary. The rule is that monthly loan repayments should not exceed a third of one’s net income.

Kenya’s public debt will have risen from 51.7 per cent of GDP in June 2013 to 54 per cent by June this year.

Judy*, a Government official who spoke to Business Beat on condition of anonymity, added that 40 per cent of Kenya’s domestic debt, which currently stands at Sh1.2 trillion, matures in February 2015. This works out to about Sh449.63 billion, with an additional Sh45 billion in interest.

Judy said about 26 per cent of this domestic debt is held in Treasury Bills (Sh316.25 billion), with 14 per cent being in Treasury Bonds (Sh133.38 billion).

This will pile more pressure on the Government to find money as signs are that revenue collection targets may not be met.

Tax base

However, Government debt is not always a bad thing.

Unlike an individual who borrows money from a bank and has to repay it, Governments do not have to pay back, as argued by Paul Krugman, an American economist and Nobel Prize winner.

“For while debt can be a problem, the way our politicians and pundits think about debt is all wrong, and exaggerates the problem’s size,” wrote Paul Krugman in The New York Times in 2012, when there was raging debate on America’s growing debt.

“Governments need to ensure that their debt grows more slowly than their tax base.”

Mr Krugman continued: “Taxes must be levied to pay the interest, and you don’t have to be a right-wing ideologue to concede that taxes impose some cost on the economy, if nothing else, by causing a diversion of resources away from productive activities into tax avoidance and evasion.”

Here is where Kenya’s debt becomes a concern.

First, the tax base is not increasing. And as the national and county governments increase their taxes, more Kenyans will either try to avoid or evade them.

Further, in the six months to December 2013, the Kenya Revenue Authority failed to meet revenue collection targets by Sh28.6 billion.

The Government received a total of Sh460.6 billion against a target of Sh489.6 billion. Treasury said the underperformance was in respect of Sh10.4 billion in ordinary revenue — exclusive of the railway levy — and Sh18.2 billion in Appropriations-in-Aid (AIA), or what ministries and State agencies generate as own revenue.

With this shortfall, a number of projects were hit in the first six months of this financial year due to the lower absorption of funds from external sources.

Sensing trouble, the Government has since come up with austerity measures that will apply to State officers to cut unnecessary spending.

But is there another option?

“Nations with stable, responsible governments — that is, governments that are willing to impose modestly higher taxes when the situation warrants it — have historically been able to live with much higher levels of debt than today’s conventional wisdom would lead you to believe,” said Krugman.

So is the Kenyan Government stable and responsible enough to increase its taxes and debts?

Following last year’s elections and a smooth, albeit tense, transition to President Kenyatta’s Government, there seems to be some stability in the national government. But county governments are not yet on solid ground.

“Our political risk rating on Kenya remains at a low and is likely to stay at a low in the short to medium term. As of writing, it looked clear that the International Criminal Court case against President Uhuru Kenyatta and probably Deputy President William Ruto may as well be withdrawn — it is just a matter of how much time the ICC needs to save face,” wrote NKC Independent Economists, a privately owned political and economic research unit based in South Africa, in their report on Kenya dated February 2014.

Living on loans

The second reason we need to be concerned about the country’s debt is because Kenya is behaving rather like many of its middle class citizens who take out loans to buy cars, furniture and other luxury items that do not bring in any income.

In Kenya’s case, seven out of every 10 shillings in the country’s Budget goes towards recurrent expenditure — paying for items like salaries and tea in State offices.

This leaves infrastructure, health, education and other public investments and service delivery projects starved of cash.

But even as spending pressures rise, especially with the transition to the devolved system of government, the revenue side has not been performing well enough to fund our growing needs.

KRA’s revenue target for this financial year that ends on June 30 is Sh973.5 billion. But by then, our debt will be at Sh2.2 trillion.

The country could easily slip into financial distress if it does not tame its expenditure, which would consequently reduce the need for borrowing.

“The public debt question remains a major source of discussion due to its growing level and potential negative impact on the country,” Mr Einstein Kihanda, the chief investment officer at ICEA LION Asset Management said.

“The high amount of debt means that there is little money left over for development (such as infrastructure), which raises concerns about long-term debt sustainability, particularly when meeting revenue collection targets remains a challenge. If left unchecked, the high public debt will raise the country’s vulnerability to adverse external shocks such as was experienced in 2011.”

In that year, interest rates hit new highs, consumer prices went up and the shilling tumbled to a low of Sh107 against the dollar.

However, Mr Kihanda says the amount of maturities due for repayment next year should not be cause for concern because the trend is for the bulk of the cash to be rolled over. This means the Government can issue new securities (T-Bills and Bonds) to pay for the debt that is due, allowing it to duck the bullet of poor cash flows, at least for now.

Good debt?

But where is the borrowed money going?

“If we are borrowing to spend on capital such as infrastructure and machinery, the debt would be good for both current and future generations. But as things stand, we could be borrowing to fund recurrent spending since that is what most of our Budget goes towards … this is not good for the country,” said John*, another source who works in one of the ministries.

There is also the burden of interest repayments. At the current levels, Kenya reels from the high cost of servicing growing debt, a situation that raises borrowing, which in turn increases interest rates.

A high interest rate environment would eventually crowd out the private sector from the debt market. This tends to dampen investment and increase the costs of doing business.

And the longer the Government keeps debts in its books, the higher its costs.

Assuming the country borrowed its Sh2.2 trillion debt at 10 per cent interest (some was more expensive, some was cheaper), it means it would pay Sh220 billion in interest alone in one year. This is more than six times the Sh30 billion set aside for development expenditure in the education sector this financial year.

Treasury has already admitted that there is trouble ahead.

“A close examination of the repayment profile indicates a significant level of both refinancing and rollover risk, with 26 per cent of the domestic debt stock maturing in the next 12 months,” reads the Medium Term Debt Management Strategy 2014 February report signed by Treasury Cabinet Secretary Henry Rotich.

So when does debt become too much?

Dr Joy Kiiru, a lecturer at the University of Nairobi’s School of Economics, says domestic debt ceilings need to be looked at in the context of GDP.

“Low levels of domestic debt can stimulate economic growth, but high levels are obviously very bad,” she said.

“The trick is to calculate the tipping point for domestic debt and GDP. This is the point beyond which more debt would hurt the economy. Basic econometric models can do that.”

But Kenya has been building its debt stock rapidly.

“The Government’s has been rolling over its debts over the past three decades ... Kenyans are being sunk into a debt trap,” said Judy.

To understand her sentiments, she explained that Kenya’s debt works the following way:

In the first year, the Government borrows A; in year two, it borrows amount B, but also amount A and A’s interest (A + Ai + B); in year three, it goes for A+ Ai + B +Bi +C, and on and on the debt spiral continues.

The trouble is that revenue is not catching up with spending; in fact, the gap is getting wider. In economic jargon, this is a situation called running a fiscal deficit.

International lenders are alive to the numbers that signify a poor borrower. This means that if Kenya seeks money from them, it will get it at much higher interest rates that more stable economies like Nigeria and Botswana that borrow in single digits.

Inflation

Another looming danger for Kenya’s economic and debt management is inflation, which NKC Independent Economists see as a big risk to the country.

According to the South African analysts, inflation will increase because of lower-than-average agricultural production, which means the country has to spend a lot more on food by importing it.

According to Judy, food holds the solution to Kenya’s fiscal woes.

“The majority of Kenyans spend more than 50 per cent of their incomes on food. If the cost of this came down, it would free up money that the Government could tap into through taxes, and few of us would complain,” she said.

John adds that Kenya must implement and stick to fiscal rules that impose discipline through long-term spending caps.

Another solution is for the Government to increase its revenue base. And since increased taxation is not the most viable of options at the moment, Kenya’s resources are the next best thing.

Kenya’s mineral wealth has captured our imagination, and that of international investors. The Government must ensure that none of this goes outside Kenya’s borders for free, Judy said.

She added that fees collected from regulatory and licensing bodies, such as the Communications Commission of Kenya, should go towards paying off interest on existing loans, rather than “paying for expensive workshops and professional courses abroad.”

* Names changed to protect sources’ identities.

[email protected]

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.