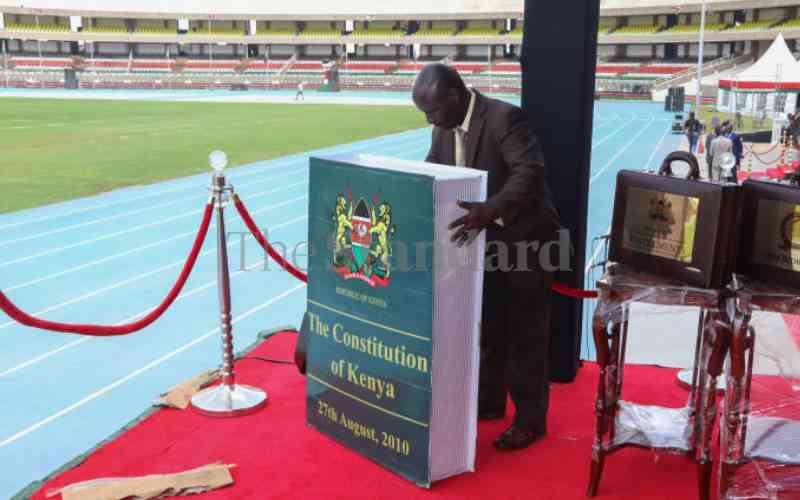

The coming into effect of a new Constitution renewed hope among the public that injustice, corruption, unfair treatment, and abuse of power by public officers would slowly become a thing of the past. To further cement the dream of a new nation, as captured by provisions of the 2010 Constitution, was Chapter Six, entirely dedicated to matters of leadership and integrity of public officers.

Were that section of the law to be fully effected then all holders of public office would be expected to demonstrate respect for the people, promote public confidence in integrity of their offices, be honest in execution of their duties, and remain accountable to the public on decisions and actions taken in discharging their duties.

While it is a fact that some change has been seen in the general operations and attitudes of public officers, there are those still reluctant to embrace the new law, particularly with regard to Chapter Six of the Constitution.

According to data from the Commission on Administrative Justice, also known as the Ombudsman’s Office, over 20,000 complaints against public officers were filed, in the past year alone. Majority of these grievances were against the National Police Service, Ministry of Lands and that of Interior and National Co-ordination, as well as the Judiciary and State Law Office.

It is believed that the number of complaints to the Commission could be higher if its reach from the current Nairobi, Kisumu and Mombasa-based offices, was widened. The complaints, ranging from corruption, abuse of power, unfair treatment, administrative injustice, unresponsive official conduct, maladministration and inefficiency of public officers, point to the hurdles that still exist in delivery of quality service to the public.

While a section of public office holders remain steeped in the past, the public has become more enlightened and it is no wonder that complaints at the Commission are rising as more people embrace bodies like the CAJ as an alternative to the often long, tedious and costly court processes involved in seeking justice.

About 10 years ago, Kenya was ranked one of the most optimistic nations in the world. And for good reasons; after more than two decades in power, the Kanu regime had been voted out of office and was replaced by the Narc administration, which swept into power on the platform of reforms. That optimism would, however, begin to crumble in the wake of political squabbles that widened schisms among the nation’s 42 tribes, eventually erupting into the chaos triggered by a disputed presidential election in 2007.

To find answers to what led the country to the edge of such an abyss, commissions of inquiry were formed and a raft of recommendations made. Overall, the rallying call from the public pointed to the need for reforms in all sectors of governance.

While there was generally a consensus on the need for these reforms in the economic, social and political spheres, the pace of implementation remains wanting. Corruption still thrives in almost every sector of public office, radical reforms envisioned in the country’s security organs remain largely on paper, and political patronage in appointment of public officers still holds sway. None other than the highest offices in the land has openly disregarded the law on several occasions, raising questions on the leadership’s commitment to uphold the Constitution.

The Constitution is clear that authority assigned to a State officer vests in that officer the responsibility to serve the people rather than the power to rule them. It also behooves the holder of such an office to be objective and impartial in making decisions to ensure that they are not influenced by nepotism, favouritism or other improper motives or corrupt practices.

The law is also clear that holders of such offices shall bear personal responsibility on account of decisions they make. Whether those tasked with holding public office have internalised these provisions is anyone’s guess. Granted, disciplinary action has been taken against some public officers over complaints of impropriety. But such cases remain few and far between with majority of the culprits escaping with not so much as a slap on the wrist.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.