By John Mwazemba

In his book on the post-election violence, The Road to Eldoret, journalist Tony Mochama writes something insightful about African politics.

Mochama dons the prophetic garb and hits the home-run in no-nonsense terms when he writes that, “Africa has always seemed a little apocalyptical to the rest of the world...Africa is where the entire funk happens...the wars from which funky films are made”. Apocalyptic indeed! In the history of things terrifying, the figure of murky African politics casts a poignant shadow.

The continent has been dogged by intermittent coups and countercoups, violent demonstrations and unprecedented brinkmanship between political actors.

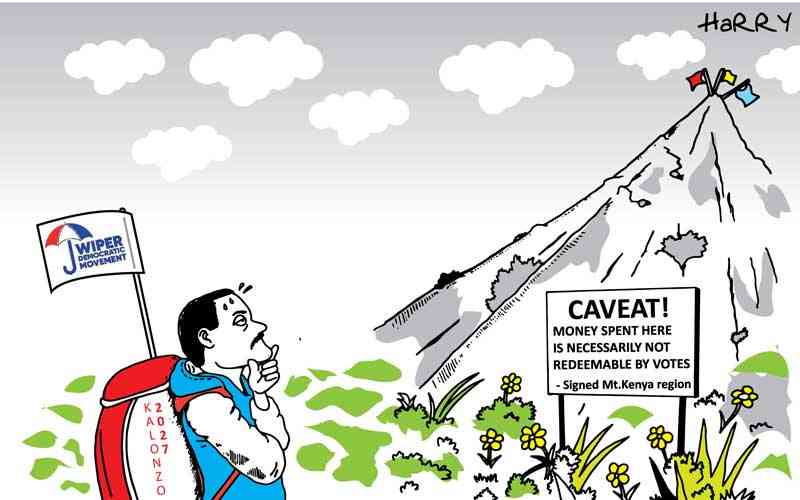

In Kenya, politics is often a cataclysmic clash of personalities, usually with irreconcilable differences, that leave behind many casualties. Whenever politicians clash, it reminds one of a hilarious poem, ‘The Casualties’ by J P Clarke. Clarke writes, “The casualties are not only those who are dead/ They are well out of it... /The casualties are not those who started a fire and now cannot put it out/Thousands are burning that had no say in the matter/the casualties are many.” At the core of all this vicious fighting, however, is a problem as old as mankind — selfishness — what we in Kenya call ‘eating’. We fight very hard because we all want to ‘eat’. Politicians fight for the cool cars and fat salaries and we fight in the belief that when our man or woman has the big seat, we’ll somehow also ‘eat’.

Chinua Achebe nails this problem in his evergreen novel, A Man of the People. In the book, when the narrator spends a night at Chief Nanga’s house — who is a Cabinet minister — he says, “I was simply hypnotised by the luxury of the great suite assigned to me. When I lay down in the double bed that seemed to ride on a cushion of air, and switched on that reading lamp and saw all the beautiful furniture...and looked beyond the door to the gleaning bathroom and the towels... I had to confess that if I were at that moment made a minister, I would be most anxious to remain one forever...We ignore man’s basic nature if we say, as some critics do, that because a man like Nanga has risen overnight from poverty and insignificance to his present opulence, he could be persuaded without much trouble to give it up again and return to his original state. A man who has just come in from the rain and dried his body and put on dry clothes is more reluctant to go out again than another who has been indoors all the time...!”

This shows that the benefits political elites enjoy become addictive — and they will do everything, sometimes even shamelessly, to advance their own cause.

We have seen this in our Members of Parliament as they have increased their salaries to obscene amounts — they are now fighting for millions in a controversial ‘retirement’ package. They have their differences but they all quickly close ranks and vote almost to a man for anything that has got to do with their getting more money and benefits. That’s what is called ‘eating’! And when a man is eating, be prepared to face the music if you try to interrupt him!

However, even voters are not entirely guiltless. In his short story, The Voter, Achebe trains his guns on the ordinary mwananchi (the electorate). He shows that citizens (who like pointing fingers at the political elite) are also just as guilty of wanting to ‘eat’. In that story, Roof, the chief campaigner for a Cabinet minister, the Hon Marcus Ibe, calls some elders at night and gives them some money to vote for Hon Marcus but they complain that the money is not enough.

Achebe writes, “Besides Roof and his assistant, there were five elders in the room. An old hurricane lamp with a cracked, sooty, glass chimney gave out yellowish light in their midst. The elders sat on very low stools. On the floor directly in front of each of them, lay two shilling pieces. We believe every word you say to be true,’ said Ezenwa, one of the elders. ‘We shall every one of us drop his paper (ballot) for Marcus...Tell Marcus he has our papers and wives’ papers too. But what we do say is that two shillings is shameful.” He brought the lamp close and tilted it at the money before him as if to make sure he had not mistaken its value. ‘Yes, two shillings; it is too shameful.’

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.