×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

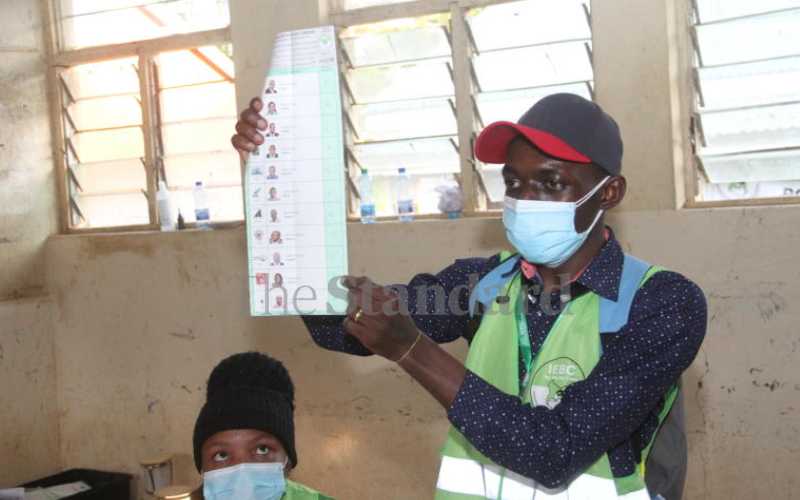

An IEBC agent counting votes during the Juja by-election, May 2021. [Edward Kiplimo, Standard]

It is likely that the integrity vetting of aspirants in this election will be a box-ticking affair. What should preserve sanctity of public office has seemingly become an artless act performed only to fulfil legal and bureaucratic electoral requirements.