×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

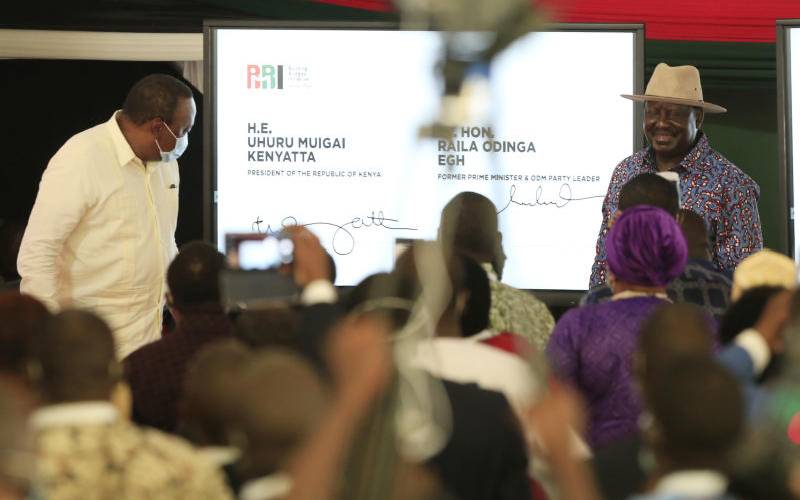

President Uhuru Kenyatta and Former Prime Minister Raila Odinga look at their signatures during the launch of the collection of signatures for the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) at KICC in Nairobi on November 25, 2020. [Stafford Ondego, Standard]

Kenya’s media, of which I am an associate member, loves the sensational. The other night a popular TV station regaled us with a story entitled “Guns Galore” in which it was claimed investigations had revealed police routinely hiring guns to thugs.