×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

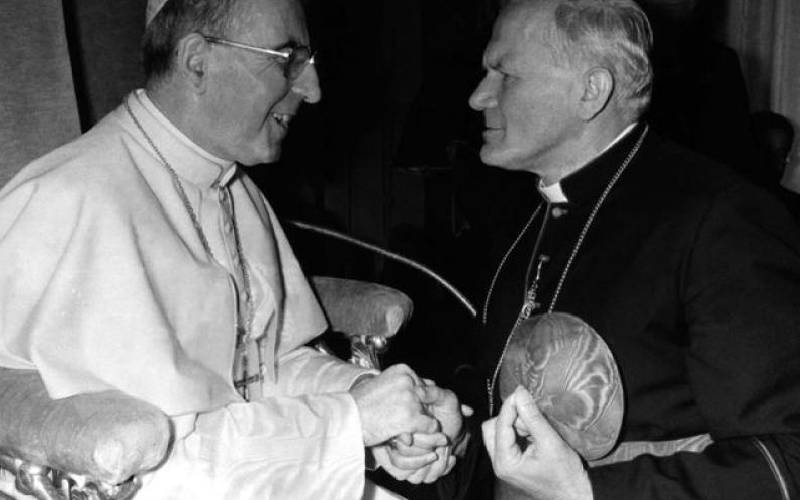

Pope John Paul I (L) meets Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, archbishop of Kracow, in October 16, 1978.

In marking the birth of Jesus Christ this weekend, let’s spare a thought for a man who meant well for developing countries–particularly for Kenya–but was never allowed to live. His name was Albino Luciani, otherwise known as Pope John Paul 1.