The honourable member of Parliament is in a quandary. Despite his high standing and the respect he commands in society, nothing seems to work, especially in his personal affairs.

For one, he is supposed to attend some bipartisan talks but chooses to let his personal assistant attend on his behalf. Not that he is very busy with state matters. Instead, he wants to have a good time with his mistress who also happens to be his secretary.

The plot thickens when the secretary's husband becomes aware of this relationship and decides to throw not one, but several spanners into the works. And the drama continues.

The above scenario might as well mirror what happens in real life among those elected to high office. This, though, was a play staged at Nairobi's Professional Centre which, ironically, is also situated along Parliament Road where the real honourable members sit.

Semeji Rau is a rib-cracking Luo comedy featuring the amorous antics of Vincent Otieno (Mhesimiwa) and his secretary played by Beryl Ruth. The comedy thrills the small audience that every so often, can be heard giggling and mumbling as the plot unfolds. At some point, it almost becomes a conversation between the actors and the audience. You do not need to understand every Luo word to be carried away.

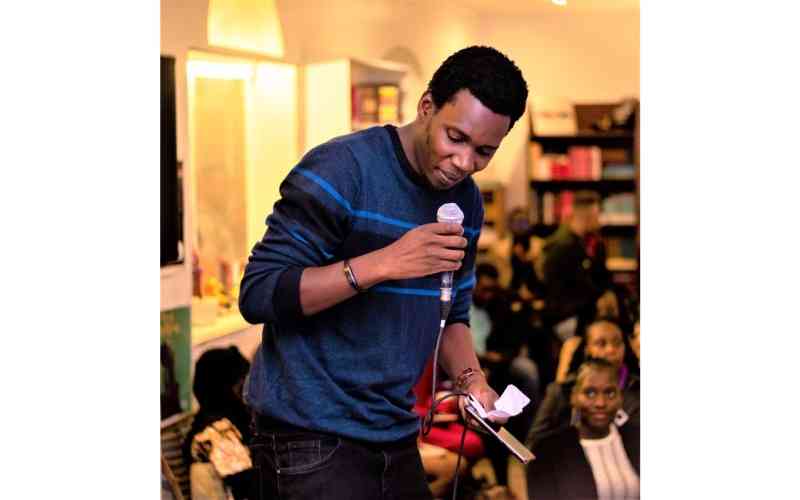

As Otieno was busy complicating his life at the Professional Centre, Emma Ofosua, the Ghanaian poet, was equally bringing the house down at the Goethe Institute with her unscripted, spoken word.

Ofosua is a freestyle artiste, one of the few who can stand on stage and stretch every fibre in her body to create words and feelings on the spot. She makes meaning out of randomness, not shallow ramblings but a deliberate connection with the audience.

At the Kenya National Theatre, Oliver, the story about a small boy who gets lost played out as the typical story of an abandoned child.

The storyline got Josephine Wanjiku lost in her emotions. She is among the young people flocking to the theatres every other weekend.

"Since I was a small girl, I have always appreciated many forms of plays, those with storylines away from the typical movies," says Wanjiku.

Welcome to the new wave raging in Kenya's theatre halls, where young audiences are willing to spend some money for a weekend of entertainment. Not too long ago, few bothered to check out what the local theatres had to offer, especially since the death of big cinema. "Post-pandemic, people are looking for outlets," says Ian Gwagi, founder and programme coordinator at Creative Spills, the outfit behind Ofosua's appearance at the Goethe Institut.

The lanky Gwagi is elated to see young blood not only packing local theatre halls but producing compelling content as well. This generation, Gwagi says, has often been written off by those who think it is more interested in technology, including computer games or spending an inordinate amount of time on social media.

"Look, these young people are educated. Sometimes we write them off but they are public intellectuals. They are looking for economic empowerment and are intentional about performing arts. They are building and documenting stories. They have a general need to be part of the community ventures, things that mean something to them," says Gwagi.

After her show at the Goethe Institut, Ofosua encouraged her audience to seek out more gigs, stating that it is possible to make ends meet out of such performances.

"It is okay to say I am an artiste and make a living out of art,' she said. "We do not have to be broke artistes, not ones who are always begging."

But in Kenya, the dwindling fortunes of performing artistes have barred many from venturing into the profession. They cite many of Kenya's most proficient thespians that have struggled to make ends meet, often surviving on handouts from friends despite their acts garnering national, and at times, international acclaim.

Gwagi says a big part of the blame lies with successive governments that have not put in place proper policies for the benefit of the players in this industry. A case in point is the current drive by the government to tax those in the creative industry, a move Gwagi says can dampen the spirit of those involved.

"Before milking a cow how much have you fed it?" he poses. "Before we request for taxes, we should ask ourselves how much we have invested in the sector. In other countries, creatives have government portals where they draw cash for their productions. In Kenya, we have no exportable content, unlike South Africa which has exported Amapiano to the rest of the world. Unfortunately, even a creative getting a passport here is a problem, let alone getting a visa."

The renewed interest in performing arts points to the power of the creative industry to shape opinions and policy and the politics of the day.

The current drive to the theatres is spurred by the works of people like Ngugi wa Thiong'o, who used similar performances to point out societal ills and root for a better society.

So serious were Ngugi's plays that former President Daniel Moi ordered his security team to hunt down 'Matigari', a fictional character in one of Ngugi's satirical writings, mistaking him for a political dissident.

"True, there are serious conversations through arts. Ngugi wa Thiong'o made theatre the centre of political discourse. Bob Marley influenced Zimbabwe politics," says Gwagi.

In developed countries, actors have influenced the advancement of technology in healthcare, aviation or infrastructure development.

As an example, George Lucas envisioned a modern healthcare system through his creations in his Star Wars universe. For instance, when Anakin and Luke Skywalker lost their right hands, they were replaced with robotic arms.

Taking the cue from Star Wars, the Mobius Bionics and the University of Utah created a real-life version of the robotic arm that enables a person to perform delicate acts such as picking an egg or peeling a banana.

Gwagi says the same can be replicated here if we take seriously the inventions of young creatives.

"Star Wars has influenced medical science. We have the potential and incredible space where young creatives can have a similar influence here in Kenya. But then we have to develop a culture where people will use disposable income for the shows. Attending the shows should morph into a general Kenyan culture," he says.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.