×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

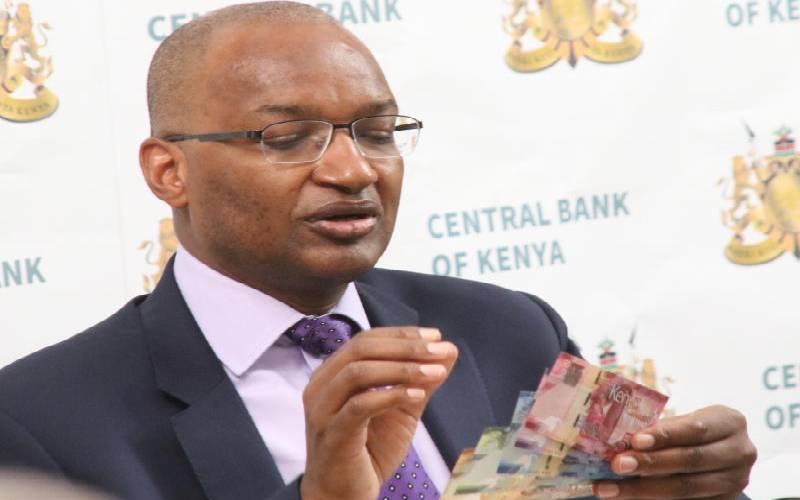

Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) will be under pressure to tell an eager nation whether it recovered all the 217 million pieces of the old Sh1,000 notes and netted a few crooks in the four-month demonetisation exercise.

This notwithstanding, Kenyans bade farewell to the elephant-embossed currency, which some proudly said had served them well in the last 25 years, but which quickly turned into a badge of dishonour to others.