NAIROBI: Kenyans will look back at 2015 as the year of hardships owing to shocks in the financial markets that caused a slump in the value of the home currency and a spike in interest rates.

On this day last year, the US dollar was selling for Sh90 while most borrowers were repaying bank loans at below 18 per cent. Now, the dollar rate is above Sh102 which some sceptics are now terming as the new normal that ordinary Kenyans should learn to live with.

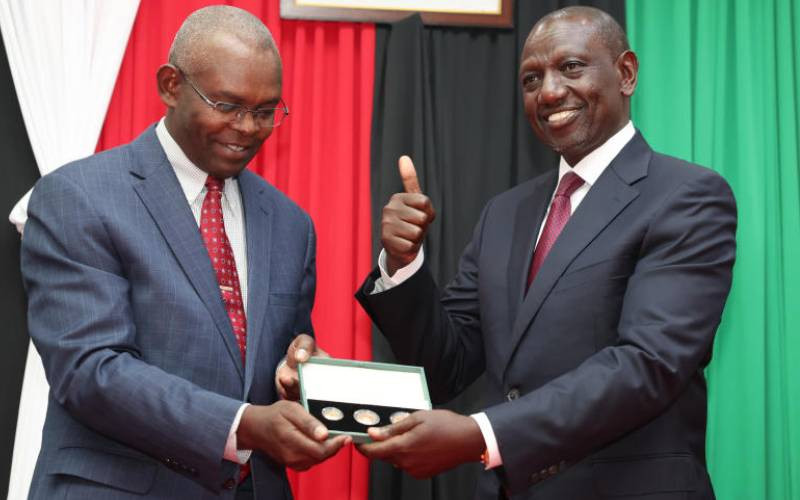

“I cannot quite call it that (the new normal) because we stand for a flexible foreign exchange policy,” Central Bank of Kenya Governor Patrick Njoroge said in his final press conference for the year last week.

Every possible intervention had been taken to keep the value of the shilling where it is, he added. On the cost of borrowing, the top banker expressed his dissatisfaction on the prevailing levels — which are anywhere about 24 per cent depending on which lender you ask.

LONG-TERM REVIEW

“Commercial banks should take a longer view in the decisions,” he said before teasing lenders that they see the future as a ‘series of short-terms’.

Borrowers we have spoken to in recent months expressed their anger over the higher repayments following the rise in interest rates. Many who had plans to borrow have shelved them indefinitely.

CBK does not have the power to direct how much commercial banks should charge on loans. But to tell how much life got tougher in the last 12 months, look no further than the cost of importing the same vehicle now and then.

Car dealers have said that the vehicle prices have jumped by more than a tenth on the depreciation of the shilling alone. A prospective buyer said he would have to save for several more months to afford the private car he has hoped to acquire by the end of 2015.

“It feels like the target is moving,” Kelvin Omari said of his aspiration to drive his own car before he turns 30. While a car might not feel like a must-have for some, it is a basic need for many—at least going by conversations among most young and newly-employed professionals.

But it is not just cars that are paid for in dollars. Kenya imports many commodities, including machinery and fuel, and any price shocks are passed on to the final consumers.

Statisticians have said that the poorest in the society are disproportionately exposed when prices are raised. The reasoning behind that is their spending power is very small and has little capacity absorb any shocks.

Further, the prices of foodstuff tend to fluctuate far more than any other commodities. Away from pain and tears of borrowers and other ordinary consumers, the problem is much bigger, and almost definitely beyond the understanding of victims.

A sustained slowdown in the inflows of foreign currency through key sectors like tourism ensured a shortage of available dollar reserves. Brighter prospects in the major economies including the US worsened the situation with foreign investors taking away their money back home.

This raised the demand for dollars, with the resultant depreciation of the shilling. Not even the Government is spared from the effect of a weakening shilling because a significant portion of its loans are in foreign currency.

A $1billion loan at the end of last year was worth Sh90 billion, but the same facility is Sh102 billion now. When the value of the dollar fell to Sh106, nearly the record low, that loan would be worth Sh106 billion.

It is for that reason that the CBK took policy interventions and averted further depreciation, including the decision to raise key interest rates in anticipation of attracting foreign investors to bring back their cash.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

Commercial banks, which the CBK boss accuses of overreacting, took the cue and raised interest rates by between eight and 12 per cent to the pain of borrowers. Top officials in the National Treasury anticipate that 2016 will be less tumultuous and that interest rates will fall to offer reprieve to the ordinary citizens.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.