×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

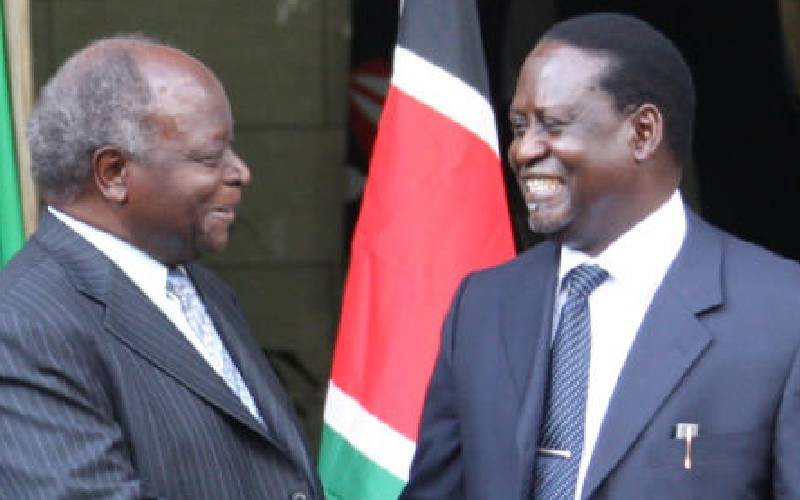

The Raila Odinga-Mwai Kibaki handshake that marked the end of the 2008 post-election violence. [File, Standard]

In our third serialisation of Oduor Ong'wen's autography Stronger Than Faith: My Journey in the Quest for Justice, the author recounts how President Mwai Kibaki and Prime Minister Raila Odinga took six weeks to form a bloated Cabinet weighed down by vicious skullduggery, suspicion and backstabbing