×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

Amid the removal of the cap on campaign funding by the High Court, a peek into Kenya's past shows politicians have always been hungering to use taxpayers to fund their campaigns.

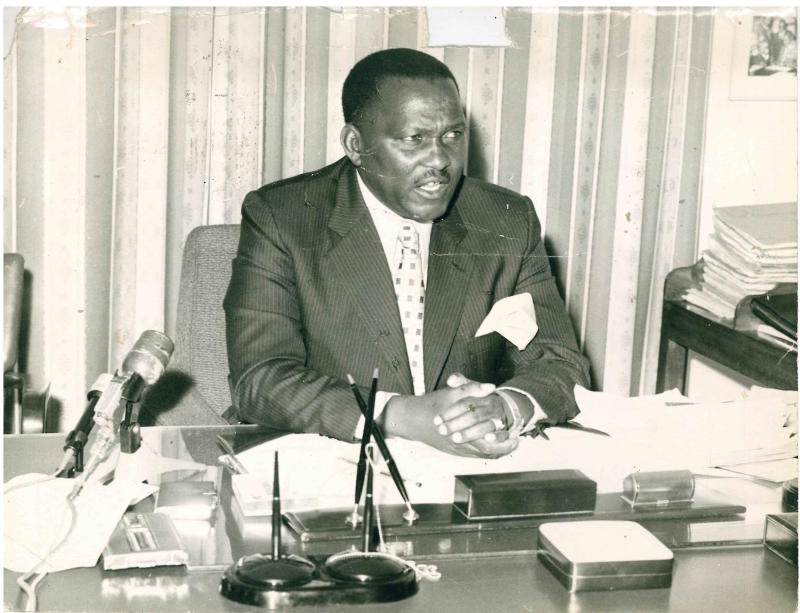

One of the most daring assault of the public coffers was executed on July 4, 1969, by the Leader of Government Business in Parliament, Paul Ngei. The timing of the Motion was telling. It was a day before Tom Mboya was assassinated.