×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

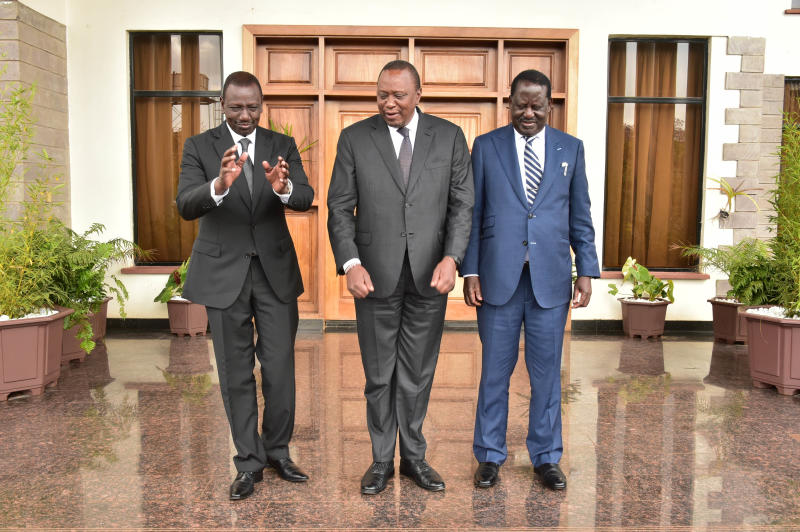

Do they say what they mean? President Uhuru Kenyatta, Deputy President William and former Prime Minister Raila Odinga at a past function. [File, Standard]

The raging debate on constitutional reforms exposes the doublespeak from the country’s top leaders, given their positions during the writing of the Constitution in 2010.