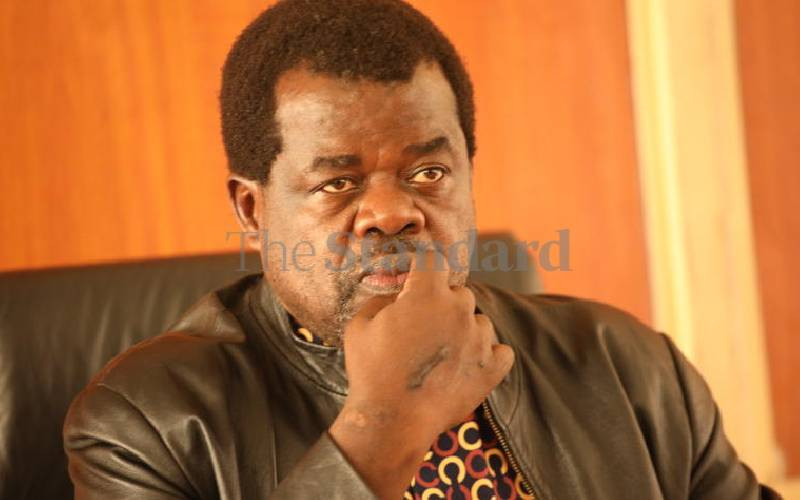

NAIROBI: On the evening of November 9, 2012 Okiya Omtatah was a man about town jumping over pools and puddles on a wet Nairobi night trying to get to his destination.

“Two men walked behind me. As we neared I&M Bank Building, one of them called out my name, ‘Omtatah’. I looked back, and we waved at each other pleasantly,” he says.

“I did not stop. Somehow they quickened up and one overtook me. The other stayed behind me. The one in front then turned to face me and asked me in Kiswahili and in a very polite voice: ‘Will you withdraw the petition you have filed in the High Court over the procurement of the biometric voter registration (BVR) kits?’ I responded in English with a strong ‘No’”.

The next few minutes would be painful. “He immediately flashed something that looked like a short, thick silver stick and struck me in the face. Almost simultaneously, the other one struck me with a heavy blunt object at the back of my head. I heard an exploding sound in my head as I fell in the rain, gravely injured. They stole nothing from me,” he says. Just two days before, he had requested for extra protection from the courts. None was provided.

Meddlesome nuisance

Omtatah was rushed to Matter Hospital. “The doctor told me if I had been taken to hospital 30 minutes later, I would not have survived,” he says.

He had filed the petition to demand accountability in the procurement of BVR kits in the run-up to the 2013 elections. Although the most brutal, the incident of November 2012 was neither the first nor the last time emissaries would be sent to him over an array of petitions Omtatah has brought before the courts.

Omtatah means many things to different people. To others, he is the champion for the rights of the downtrodden. To the political establishment, he is a meddlesome nuisance and a thorn in the flesh.

Never has this been more clear than in the happenings at the Supreme Court over the last two weeks. When the top court sat to hear an appeal by former Deputy Chief Justice Kalpana Rawal and former Supreme Court Judge Philip Tunoi challenging a ruling by the Court of Appeal on their retirement, it is Omtatah’s petition that sealed their fate.

In his petition, Omtatah asked the five-judge bench of Justices Willy Mutunga, Mohammed Ibrahim, Jackton Ojwang, Njoki Ndung’u and Smokin Wanjala to recuse themselves from the case as they would be biased in their decisions having made their feelings on the retirement debate known.

“Dr Mutunga and Justice Wanjala being members of the JSC which has decreed that the judges must retire upon attaining the age of 70 years, cannot preside in their own cause,” Omtatah said in his preliminary objection.

After listening to his spirited argument, justices Mutunga, Ibrahim and Wanjala, recused themselves, effectively sending Rawal and Tunoi home after months of legal push and shove.

But it is one other case, he says, that will stick with him forever, particularly because of the names and big money involved. “Compared to it, the Supreme Court petition is child’s play,” he says.

To get to Omtatah’s office a few metres from Milimani Law Courts where he has fought many of his battles, one crosses the road, goes through the National Social Security Fund (NSSF) building into an escalator to the basement, up a flight of stair into a different wing of the NSSF complex. You then have to go down one level to his basement office. This also doubles up as a cyber café and photocopying bureau.

In spite of this, he is not a hard man to find. And people, whom he rubs the wrong way, always get to the former seminarian. Somehow.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

“The theft was obvious but the vested interests were many,” he says of the case. “I was in Mombasa and was called by two senators, one from Western Kenya and another from the Rift Valley. They called me for a meeting but I told them I was in Mombasa. They sent me a plane ticket alluding to the urgency of the matter. I obliged and we met at the Laico Regency Hotel. They told me that the various parliamentary committees involved were already aligned to the matter and that Sh200 million had already allegedly been paid out to them,” Omtatah says.

The two senators then asked him what he wanted, saying whatever he mentioned would be met.

His petition was dismissed in what he terms ‘unclear circumstance.’

“The government filed a cross petition. How can a government file a petition against a civilian? If I had done anything bad to the state they ought to have used the penal code against me. The role of the petitions is to uphold the constitution. This is the mediocrity that the courts have sunk into,” he says.

“The overzealous judge said the petition had no supporting evidence even though the documents documented the loss of Sh46 billion.”

But it was during the BVR kits case that he understood how, sometimes, puppeteers blatantly influence decisions in court.

“When I made the application to stop the procurement of the BVR kits, the Attorney General was forced to bring evidence showing that procurement procedures were properly followed. But the evidence they brought was a computer printout with no signatures. When I raised this issues, the judge adjourned and when he came back, the documents had been signed. But they were not sealed. So I raised this issue again. He adjourned the court again. When we came back, the documents had a seal,” Omtatah says.

“Okiya you will come here until you get tired,” the judge told him. I told him I would go to the courts until I got justice, he says.

But he has not lost hope in the much blighted judicial system yet.

“We have new and young judges bent on upholding the law and building credible reputations. They are the ones who will make a difference,” he says. “The justice system should be our last line of defense. Even in a space of retrogressive politics, the courts should always be progressive.”

He still wants to be Senator. In 2013, he vied in Nairobi. In the next general election, he will go for the same seat but away from the capital.

“Nairobi elections are presidential. For you to succeed, you need either (CORD leader) Raila Odinga or (President) Uhuru Kenyatta to hold your hand. I am not cut out for that.”

Six desktops, rows of paper files, an ever buzzing photocopying machine and one laptop make up his office. It is here that he reads from and researches on matters of public interest. But public interest is almost always in conflict with private enterprise. Mostly, the conflict is in terms of big money and power. Is he afraid for his life?

Strong faith

“Life can only be preserved by God. It is to Him that I owe my existence. We were not born to fret over death but to thrive in life,” he says. His strong faith can perhaps be attributed to his years at St Peters Seminary Mukumu. After his secondary education, he turned down a call up to the University of Nairobi to study for a Bachelor of Commerce degree and opted to study philosophy at St Augustine Major Seminary in Bungoma.

Litigation is expensive. How does he fund his cases? Does he push other people’s agendas?

“I fund everything I do on my own. If I were paid by other people, I would eventually be conflicted,” he says. His money, he says, comes from royalties from his published books and a thriving cereals business.

“Ten per cent of everything I make goes towards this cause. When you come into the world, change something, even if it means just removing a thorn from the road so that he who has no shoes doesn’t get pricked by it.”

So far, the ex-seminarian, father and husband has filed 69 petitions of public interest, some going on. Forty five others have already been determined. “Upholding the constitution is my drug. It’s more than a hobby to me.”

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.