×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

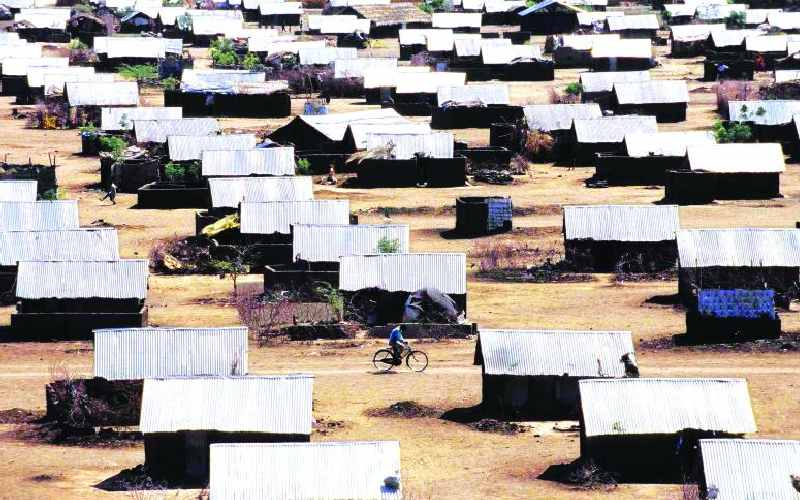

Kakuma Refugee Camp hosts about 200,000 migrants from as many as 22 countries, from the Eastern and Central African region and beyond. [File]

Today is World Refugee Day. It is 70 years since the United Nations promulgated the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees in 1951 as an international treaty on caring for persons who are out of their countries of nationality owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.