×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

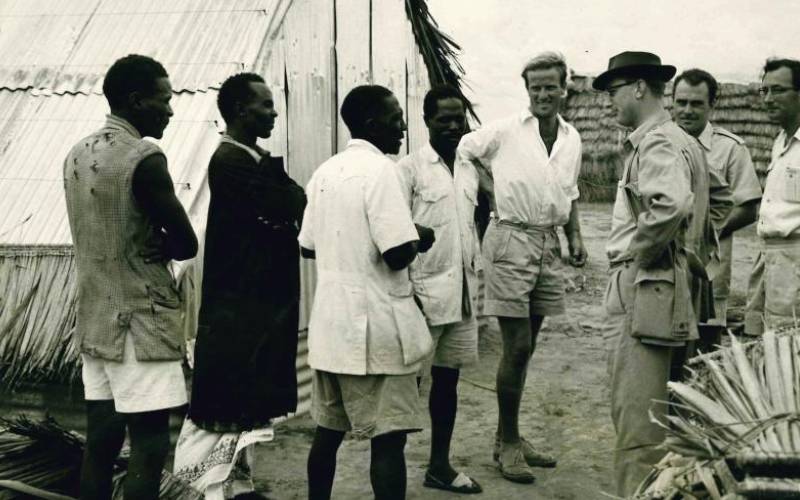

When the horrors of Hola were leaked, the government was so scandalized that it had to redeem its image. [File, Standard]

Horror stories abide of prisoners dying mysteriously in their cells. Some explanations given by their jailers are ridiculously hilarious while others are simply unbelievable.