×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

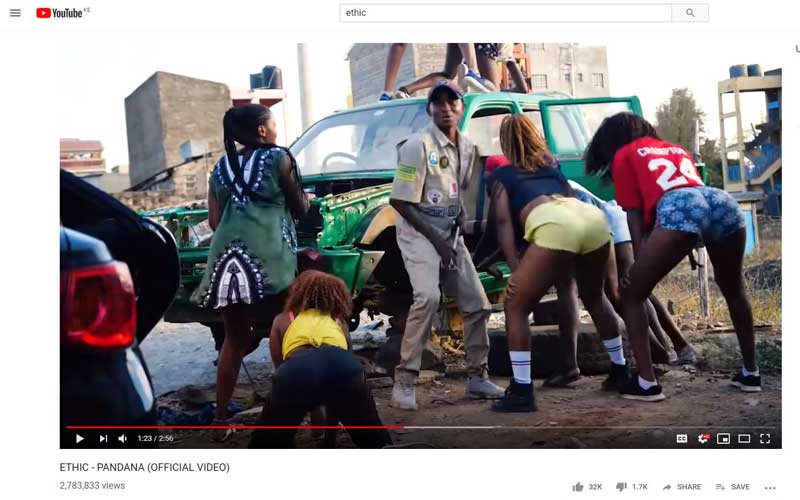

At some point in time, you have heard the chant that has taken over the streets, “Wamlambez” and the response “Wamnyonyez”.

While the two words are significantly bordering on the obscene, they go to show just how far popular culture is evolving and how what could otherwise be considered profane can be accepted as part of everyday life.