×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

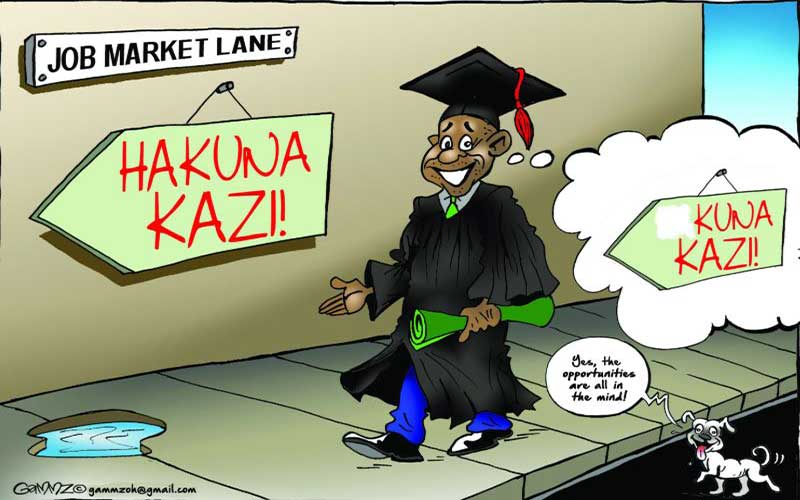

You stand a higher chance of landing a job in the food industry, with the latest official data showing that the sub-sector churned out the most jobs in four years to 2018.