×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

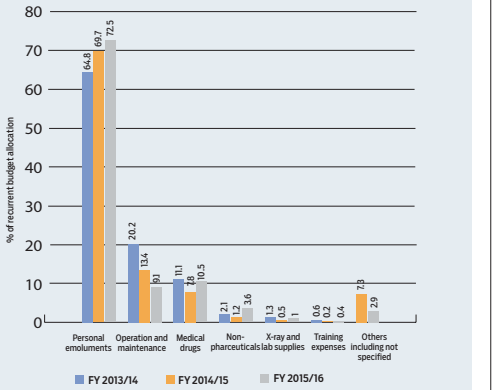

Most county hospitals cannot afford medicines, food or linen for patients as almost all their money go into paying salaries.

Salaries, low financial allocations to health, unpredictability and delayed disbursements and corruption have been blamed for the crisis in county hospitals.