×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

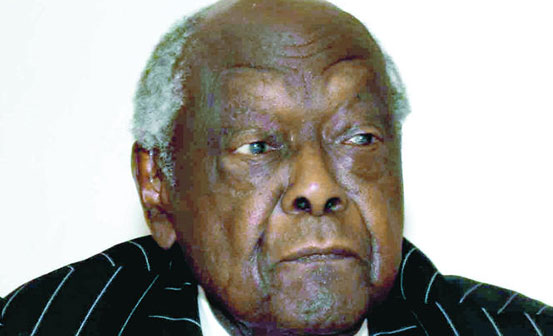

Former Judges and Magistrates Vetting Board chairman Sharad Rao has revealed the behind-the-curtains dealings that led to the fall of former powerful Attorney General and Constitutional Affairs Minister Charles Mugane Njonjo.

In a speech delivered at the UK’s House of Lords on Monday, Rao told an audience that included former UK envoys in Kenya that a controversial Indian astrologer “fixed Njonjo”.