×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

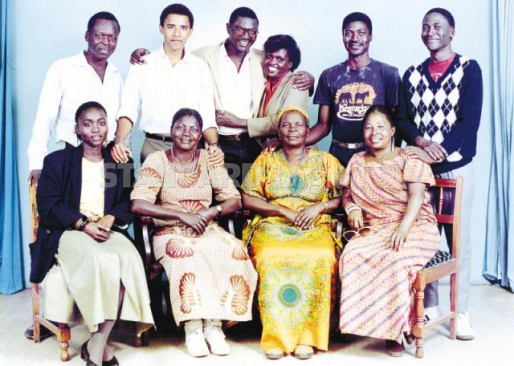

During one of his early visits, Barack Obama found himself huddled amid 15 or so people, in a congested sitting room in Nairobi’s Kariokor Estate, “all of them smiling and waving like a crowd at a parade”.