|

|

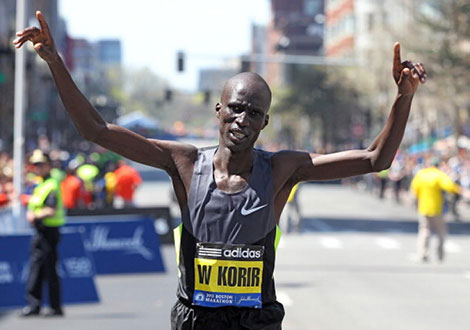

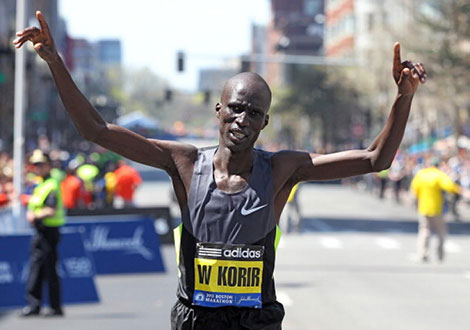

Wesley Korir of Kenya reacts after he won the 116th Boston Marathon on the April 15, 2012 in Boston, Massachusetts. (Photo by Jim Rogash/Getty Images) |

Former Boston Marathon champion and Kenyan Member of Parliament, Wesley Korir, plans to introduce a bill to criminalise doping in Kenya.

The 2012 Boston Marathon winner made the announcement on his Twitter feed, just weeks after revelations that one of Kenya’s most renowned marathon runners, Rita Jeptoo, tested positive for erythropoietin (EPO) prior to her victory at the Chicago Marathon on October 12.

“I will be introducing a bill in Parliament to criminalise doping in Kenya to athletes, agents or doctors that assist athletes dope,” Korir wrote.

“If the bill passes the athlete will be forced by law to give up the source of drugs or face jail time and will be fined and banned for life.”

The 32-year-old added that he would be meeting with officials from the Professional Athletics Association of Kenya (PAAK), a new athletes’ group in Kenya chaired by reigning London Marathon champion Wilson Kipsang, this weekend to discuss more about the bill.

Germany Example

Korir’s bill will follow in the footsteps of a similar piece of legislation put to the Bundestag in Berlin on Wednesday (November 12).

This proposed law would see doping criminalised in Germany and include jail terms of up to three years for elite athletes found guilty of taking performance-enhancing drugs.

News of Jeptoo’s failed doping test rocked the athletics world when it came to light on October 31 and topped what has been a torrid two years for Kenyan sport.

Over the past two years, more than 30 athletes from Kenya have failed doping tests, arguably tainting what is a national source of pride for Kenyans.

World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) President Sir Craig Reedie has expressed strong reservations about Germany’s proposed new anti-doping law, saying WADA is “completely opposed to the criminalisation of athletes”.

While the agency does favour criminal penalties for drug dealers, coaches and other members of an athlete’s entourage found guilty of serious transgressions, Sir Craig said existing sporting structures, developed over a number of years, should be left to deal with offending athletes.

He held up Italy, where doping in sport has been a criminal offence since before the Turin 2006 Winter Olympics and Paralympics, as an example of good practice.

“While the law has proved itself to be an effective tool in the fight against doping, no athlete in Italy has ever been subject to criminal prosecution,” Sir Craig said. “That’s the way it should be.”

Sir Craig also emphasised the need for legislation to permit the transfer of information between agencies and the use of investigative powers by law enforcement bodies.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

His comments come in the wake of last week’s news that Germany may next year present a proposed law to its Parliament that would include the possibility of jail terms of up to three years for professional athletes.

About 7,000 German professional athletes who are covered by the national testing programme would be affected by the new law, which would not extend to recreational athletes.

There has been a chorus of calls for tougher penalties for drug cheats in recent years. A new World Anti-Doping Code extending to four years ban for athletes found guilty of serious doping offences for the first time, is due to come into effect on January 1.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.