×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

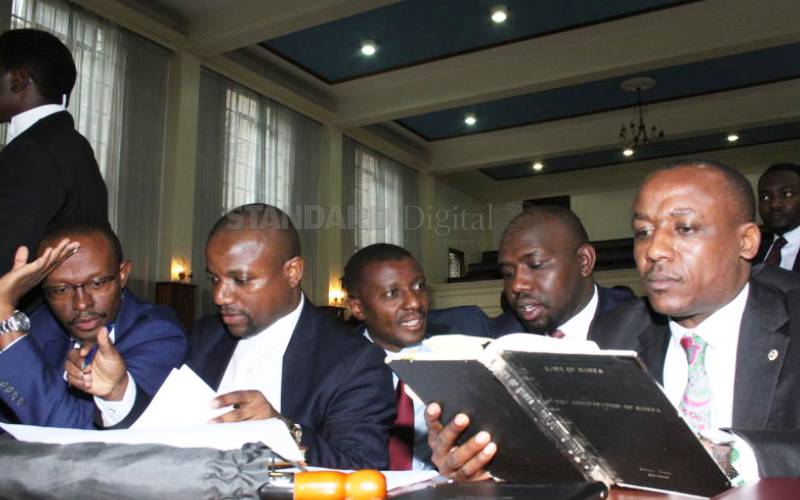

Defence lawyers Cecil Miller, George Kithi, Dan Maanzo, Kipchumba Murkomen and Mutula Kilonzo Junior at the Milimani court. [Collins Kweyu]

Last week, senators Mutula Kilonzo and Kipchumba Murkomen, who is also Senate Majority Leader, appeared in court to represent Nairobi Governor Mike Sonko in his corruption case.