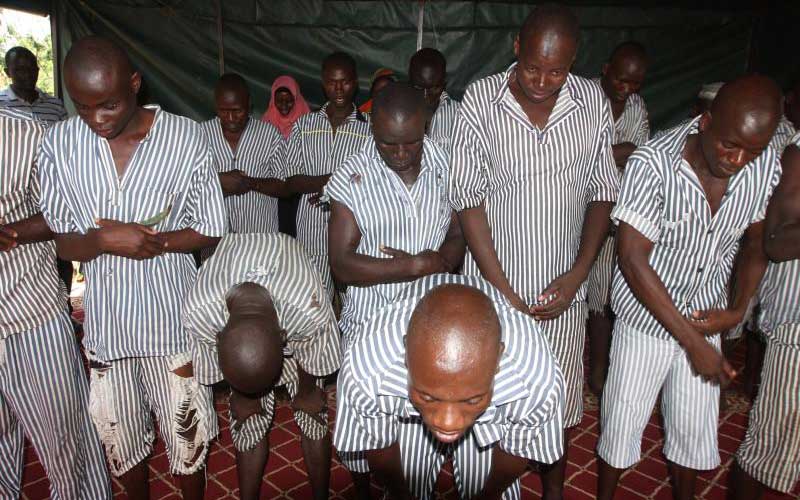

Reflect for a moment what it would be like to be released from prison with no money to a community that is frightened of you having served a 20-year sentence. I was shocked that we don’t have more of half-way homes for the thousands that leave our prisons each month.

A quick review of prison data exposes our criminal justice system to be a large revolving door. The police and county askaris arrest two million people every year. Two thirds are arrested for petty offences such as being drunk and disorderly, unlicensed trading, sex for payment, fighting, petty theft and fraud.