×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands of Readers

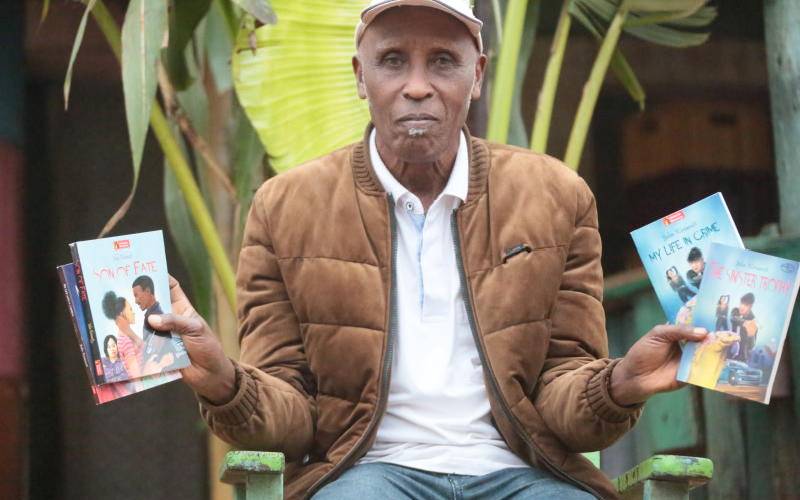

John Kiriamiti at his in home Kiria -Ini in Murang'a County. [Kibata Kihu, Standard]

The first time we met, I was astounded by how youthful John Kiriamiti looked. That was in Murang’a two years ago.