×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

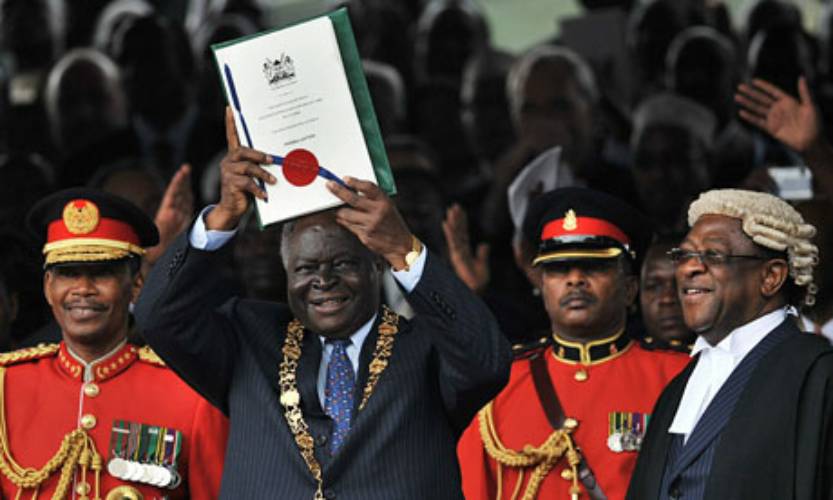

Independent Kenya’s original constitution was a product of the Lancaster House negotiations between the British Empire and Kenyan representatives.

Like other former colonies in Africa, Kenya soon embarked on a process of constitutional amendments that at the time seemed necessary to realise full self-governance and sovereignty.