×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

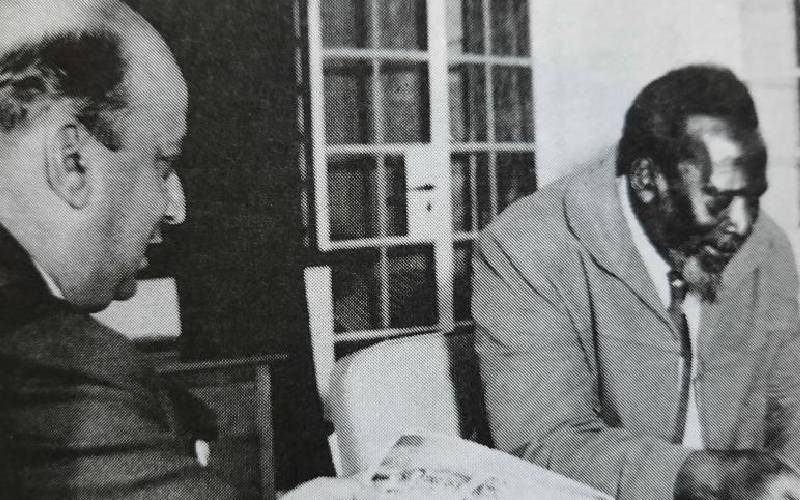

On April 12, 1960, a heated debate ensued in Kenya’s Legislative Assembly. It started when local government minister Sir Wilfrid Havelock urged the House leadership to adjourn proceedings and discuss the strike proposed by the Nairobi People’s Convention Party (NPCP) for the release of Jomo Kenyatta.

The NPCP had proposed to lead the national strike on April 15, a Good Friday.