Nigerian biographer Babafemi Badejo has described opposition leader Raila Odinga as “an enigma in Kenyan politics” and written a book with that title. I don’t know what the Nigerian writer meant by “enigma”, but I can tell you the impressions I had of Raila on the four occasions I met him.

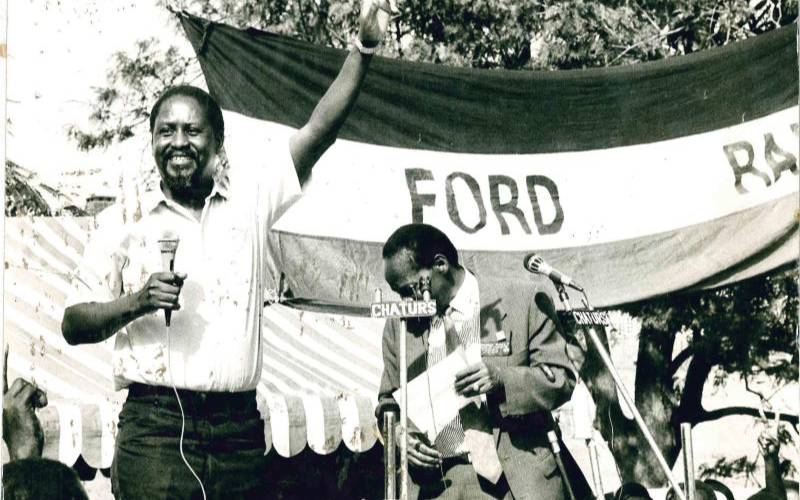

My first one-on-one meeting with Raila was in August 1992. I was working for a media consultancy firm called Pentaline Services, which had been contracted to work for presidential candidate Kenneth Matiba in the elections that year. Raila was deputy director of elections in Ford Kenya party on whose ticket his father, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, was the presidential candidate.