In Kinyach location of Kerio Valley, Baringo County, school children happily harp a song from a popular Psalm.

“I lift up my eyes to the mountains. Where does my help come from? My help comes from the Lord, the maker of heaven and earth.” (Psalms 121)

The mountains of Elgeyo Marakwet sit majestically yonder, their waterfalls glittery from the shining sun. The Tugen, Marakwet, Keiyo and Pokot who reside here looked to those mountains for help when Pokot raiders relentlessly pounded on them a few years ago.

Under heavy fire, the communities were pushed to the mountains as raiders overrun the area. The mountains gave them succor but the lasting peace, they now attest, came from God, through prayer.

Schools, including Kinyach Primary which we are visiting, were closed for several years until 2012 when they were re-opened.

“Jina lako ni Barnabas Kome,” an elder who welcomed us introduced himself in ‘perfect’ Kiswahili, betraying his literacy credentials to the congregation. Everybody giggled.

Lasting peace

In the school, whose walls are laced with bullet holes, an interdenominational prayer-cum-peace meeting is being held.

The Pokots, Tugens, Marakwets and Keiyos are in attendance. Every so often, they break into a popular Pokot peace song whose chorus I easily picked: “Sere nyowou tororot aketueele asete (Thank you God for you have united us in your love today).

They all hope the peace will last forever. “Behold, how good and pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity,” Reverend Thomas Lesalaja, a Njemps, opened the meeting on a felicitous prose, his arms spread out.

Songs were sung. Testimonies given. Encouragement offered. Hopes expressed and prayers said before Samuel Chesupet carefully yanked off the ultimate secret on how peace was procured.

In these parts, secrets are peeled out like an onion. The innermost and most sensitive of secrets are spilled out last.

“We held parallel meetings as church and community elders. The two groups later converged under the trees and held candid discussions on how to restore peace,” he said.

For two days, day and night, the elders did not leave the meeting as they explored the finest of the solutions to insecurity in the area.

Eventually, they settled on an oath which cursed raiders to painfully die of snake bites or stump tree injuries if they defied.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

All Pokot youths in the region and outlying areas were summoned to take the oath. The few who defied the oath and attempted a raid afterwards died as per the oath. The other youths started to believe in the oath and kept off the raids.

“It worked so swift and fine that some parents started blaming the old men. The old men however stuck to their oath and the rest, as they say, is now history,” he said.

Nancy Lochulia, a Tugen married in Pokot, recalled how all women from communities in the area held a peace march before converging in one place and laid down their twigs to pray.

“We prayed and peace was restored. We also talked to our children. We have realised the uptake of the Gospel among our people is changing lives and perceptions about the value for human life,” she said. Almost everyone residing here lost something. During the NCIC meetings, they said although the Pokots have never compensated them, they are not seeking for any compensation.

Jackson Kiplalon, the area assistant chief, is relishing the post-oath days: “One day there was a raid in which the raiders surrounded our local dispensary. I called one of the Pokot elders and he told me to relax, that they would miss their targets. Gun fire rent the air until 11am from dawn. I was delighted when they told me no one was injured.”

Kiplalon caused laughter when he explained why Tugens would not care fighting back the Pokots: “How are we expected to fight back people who wear shukas?”

John Kipsang, our guide, who had encouraged us through the long and bumpy ride from Kabarnet to Kinyach was a victim of the raids as well.

“They pushed us to the mountains. All the homes here were closed, schools and markets too. The raiders said they will make my father’s stone house an office for their administrators. It was clearly an expansionist agenda,” he said.

Kipsang is now a peace ambassador partly working with NCIC to make peace in other areas in Baringo. He carries with him the “Kinyach model” of peace for display to communities searching for peace.

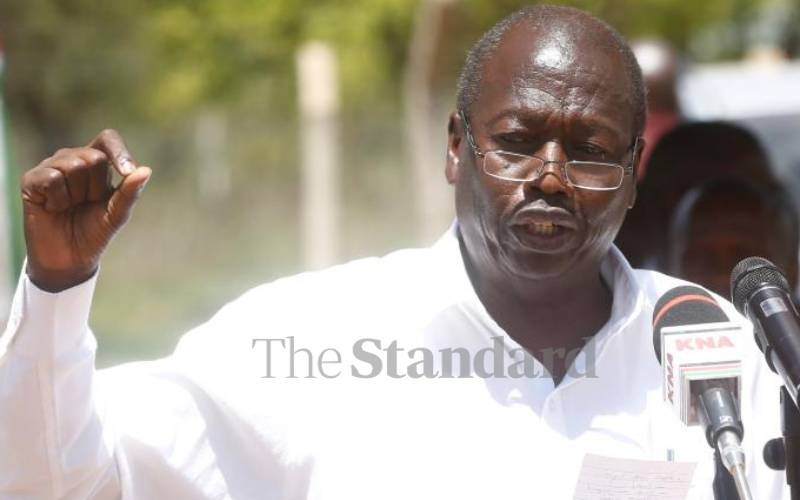

Reverend Peter Chemwaswet, the lead NCIC peace facilitator during the Kinyach meeting congratulated the communities in the area for leading the way in making of peace. He said military operations to rid these areas of raiders never solve the problems.

Elders’ say

The solution, as we learned, rests with local communities, not with batons and heavy boots.

“To the contrary, violence tends to beget violence. The use of force and heavy weaponry makes people adamant. In the process, they are introduced to new weapons and tactics of war which live with these communities for long,” Chemaswet said.

Chemaswet had been here before at the height of hostilities between the area communities. He couldn’t believe that herein were all the communities, now bound in one love, sitting together and recalling the gone days.

“I have buried several chiefs in this area. Their lives snuffed out by the arrow of violence. Our hope and prayer is that this will last forever, and that the conviction to keep peace will never fade away.”

As the sun descended on the nearby Marakwet hills, we left Kinyach with one indefatigable conviction; that in Pokot the power lies with the elders. Any peace efforts which do not target Pokot elders have a snowball in hells chance of success.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.