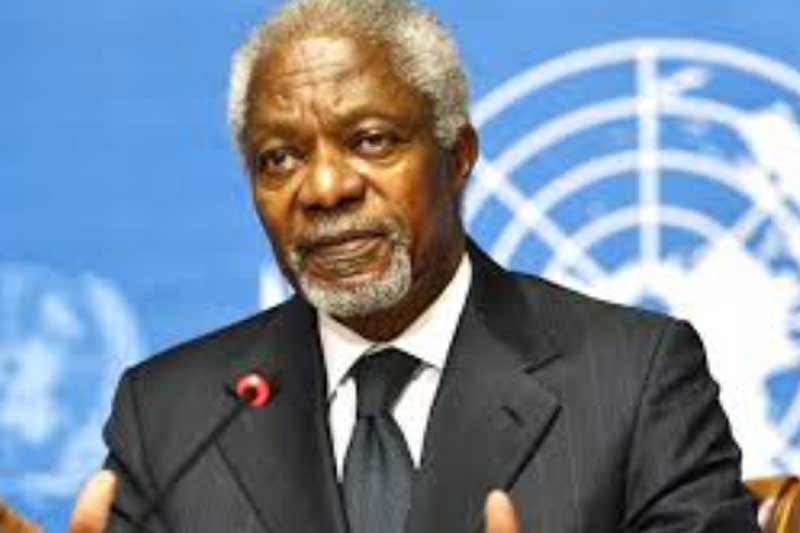

Coincidences can be unnerving. Two men, representing conflicting interests, rubbed shoulders at the United Nations. Kofi Annan, UN Secretary General, and John Robert Bolton, United States ambassador to the UN (2005-2006), disliked each other.

Mr Bolton was sneaked into the UN ambassadorship because there were doubts whether the Senate would confirm his appointment due to his hostile views on the UN. Mr Annan was a champion of the newly-created and Clinton-endorsed International Criminal Court. Bolton was a critic and wanted to destroy it. He pushed the US to 'unsign' from the ICC and masterminded the 2002 “Invasion of Hague Act”.