×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya's Bold Newspaper

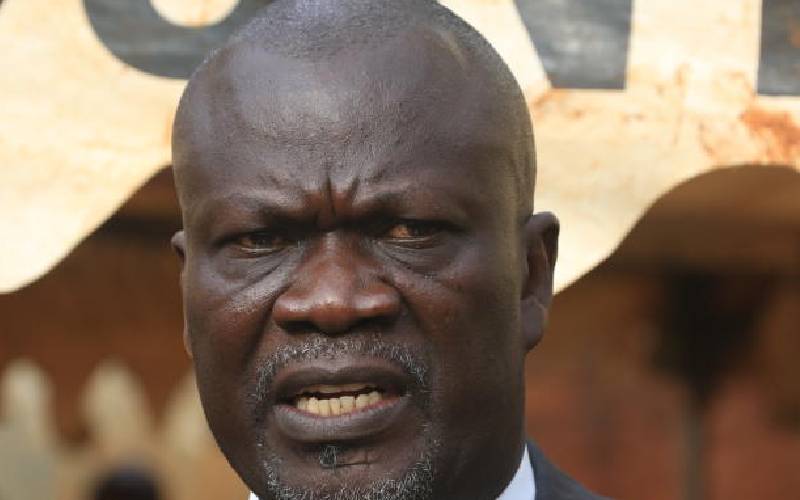

Siaya Governor Cornel Rasanga. [Collins Oduor, Standard]

This is close to home and should come as an open letter to Siaya Governor Cornel Rasanga, a man voters love so much that he has won three elections in two election cycles.