×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

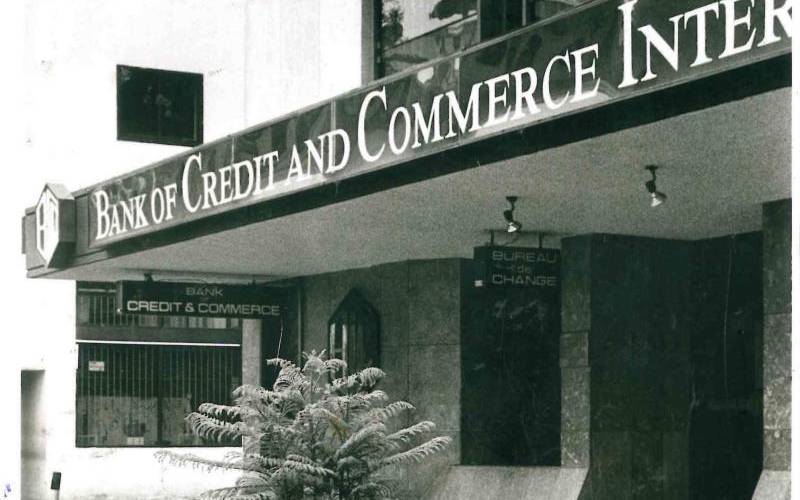

“This bank would bribe God.” These words of a former employee of the disgraced Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI) sum up one of the most rotten global financial institutions.

BCCI pitched itself as a top bank for the Third World, but its spectacular collapse would reveal a web of transnational corruption and a playground for dictators, drug lords and terrorists.