×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

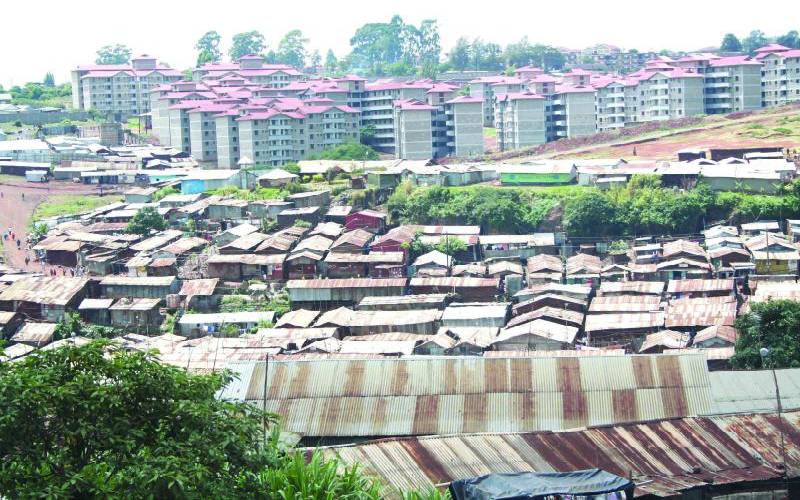

Nancy Achieng lives in Kibera on less than Sh200 a day. Money she earns by washing clothes in nearby Langata estates.

Nancy Achieng lives in Kibera on less than Sh200 a day. Money she earns by washing clothes in nearby Langata estates.

The mother of four lacks a constant supply of water and electricity and relies on illegal utility connections. She is aware of inherent dangers but with little means of survival, she is more concerned about her family’s next meal than how efficient or clean the lighting and cooking fuels are.