×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

Glass has been in existence for centuries, from as early as 1500BC. One of the most revered methods of forming glass objects is glassblowing – a hand-crafting technique in which glass is shaped by heating it to a specific degree and then blowing air into it through a tube to get the desired shape.

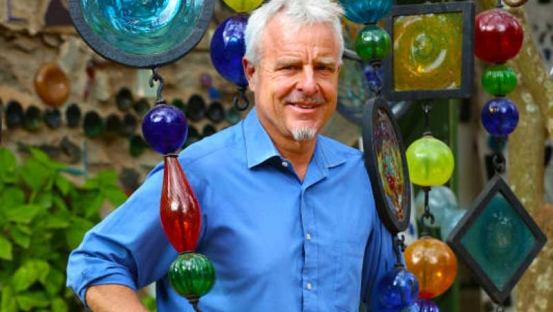

In Africa, there are countable companies that specialise in glassblowing. Among these is Kitengela Hot Glass, which was founded in 1991 by Anselm Croze and his mother, Nani.