×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

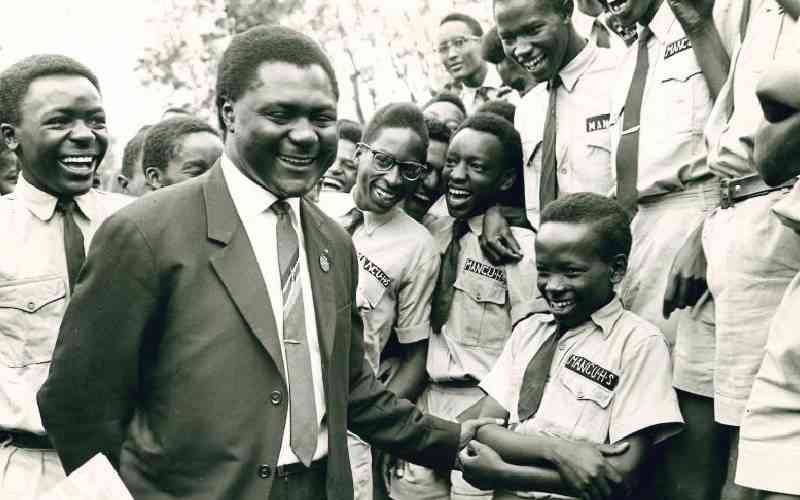

An important book by an important author is in the bookshops. It is a biography of Tom Mboya by B.A. Ogot.

Prof Ogot was a close friend of Tom Mboya and a key part of his personal political team. Most importantly, he shared an equal vision for Kenya.