×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

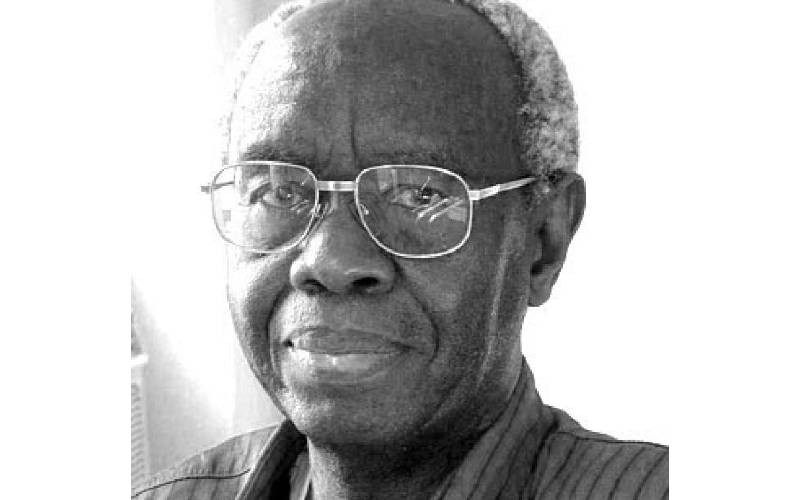

Prof John S Mbiti, who passed on in 2019, is accepted in scholarship as the father of African theology. The iconic Mbiti was a paradox.

An ordained Anglican priest, he also believed strongly in traditional African values and their place in religion, including in Christianity. One of his seminal contributions to theosophy is the notion of the living dead. But how could a person be at once living and dead?