×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

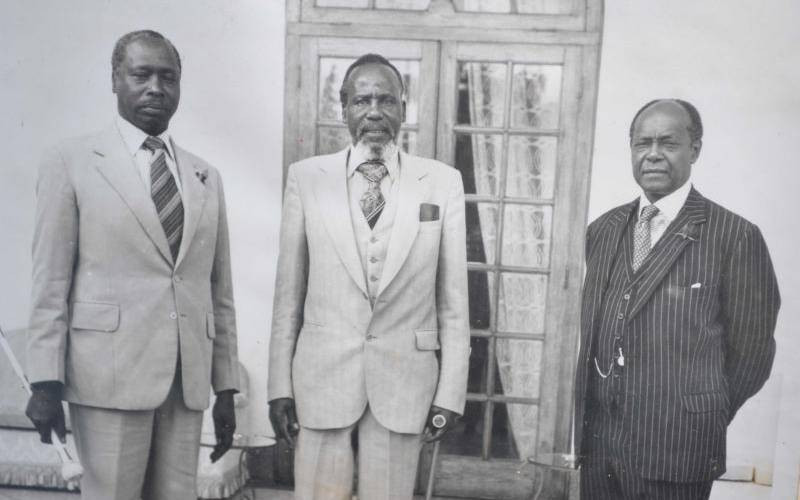

In 1982, the late "Duke of Kabeteshire" Sir Charles Njonjo was the powerful Minister for Justice and Constitutional Affairs.

Buoyed by the power Kanu had accumulated since President Daniel Moi's successful transition from Jomo Kenyatta, Sir Charles led the party in Parliament in effecting the 1982 constitutional amendment that converted Kenya into a de-jure one party state.