×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

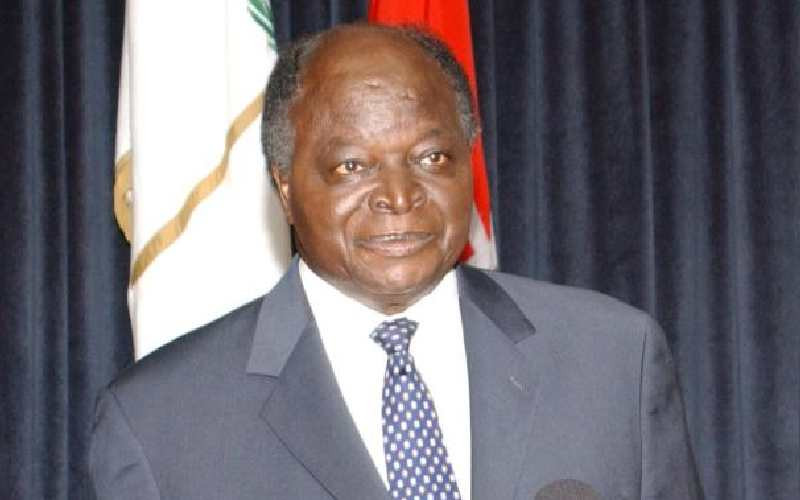

In our continuing book serialisation, author Oduor Ong'wen revisits the two controversial 2002 MoUs that drove a wedge between the Kibaki and the Raila side of the NARC government

The moment was euphoric. The feeling was ecstatic and the feel-good mood was written over the faces of many a Kenyan - and a few friends of Kenya who were here to savour the moment.