×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

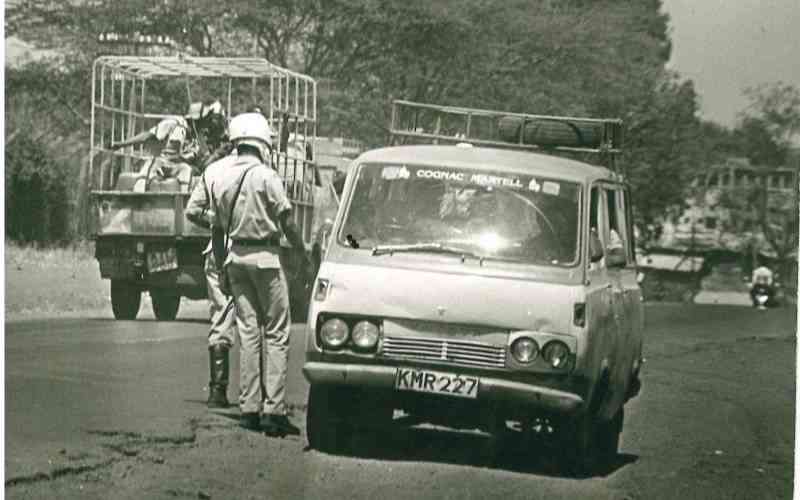

The chaotic journey that started in 1970s screeched to a halt after an 18-year-old reign. The tires of the matatu associations were punctured by Attorney General Mathew Guy Muli whose mighty pen did the unthinkable.

In one clean whorl, Muli’s mighty pen on December 6, 1988, sealed the fate of Kenya Country Bus Owners Association, Matatu Association of Kenya and Matatu Vehicle Owners Association.