×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

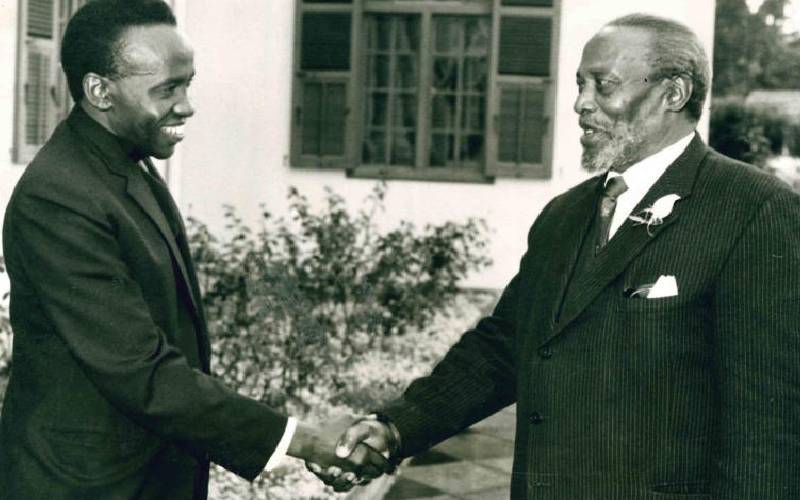

Newly appointed Bishop of Machakos Ndingi Mwana A'Nzeki with President Mzee Jomo Kenyatta in August 1969.

Nobel literature laureate Wole Soyinka famously said the man dies in everyone who keeps silent in the season of oppression. Graham Green, another Nobel literature laureate, said this is the man within – the man of conscience.