×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

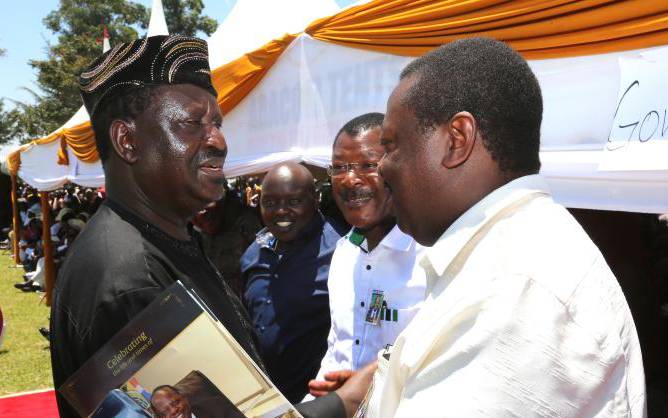

ODM leader Raila Odinga Amani National Congress party leader Musalia Mudavadi and Ford Kenya party leader Moses Wetangula in a past function. [Benjamin Sakwa, Standard]

Thrice drawn by fate to work with “the enigma of Kenyan politics”, Amani National Congress leader has finally unfurled the complex political personality of ODM leader Raila Odinga.